Put simply, a country’s current account balance measures the difference between how much it spends and makes abroad. Trade in goods usually—but not always—accounts for most of the current account, while the other components are trade in services, income from foreign investment and employment (known as ‘primary income’), and transfer payments such as foreign aid and remittances (known as ‘secondary income’).

A current account surplus or deficit is not necessarily in and of itself a good or bad thing, since a number of considerations must be factored in—for example, in the case of deficit countries, whether they make a return on their investments that exceeds the costs of funding them. A large current account surplus can be considered a desirable sign of an efficient and competitive economy if it comprises a positive trade balance generated by market forces. And yet such competitiveness can also be falsely created to an extent by policy decisions (e.g. a deliberate currency weakening), or may alternatively be a sign of overly weak domestic demand in a highly productive country. Therein lies the crux of the controversy, or at least one of many.

|

Do you want to know more? FREE white paper: Is the Global Economy Rebalancing? In addition to this post, you’ll get an in-depth look at Just click on the button below to download the white paper for FREE. |

Global imbalances were a critically important contributing factor to the financial crisis, although they did not in themselves cause it. Even if the precise nature of that connection has sparked different interpretations, there is at least more or less agreement on the fundamentals of the part played by trade relations between the U.S. and China, the two countries traditionally responsible for the lion’s share of global imbalances. Credit-fueled growth in the U.S. encouraged consumers to spend more, including on products originating in China, thereby further increasing the U.S. trade deficit with China and prompting China to “recycle” the dollars gained by buying U.S. assets (mostly Treasury notes). This, in turn, helped to keep U.S. interest rates low, encouraging ever greater bank lending, which pushed up housing prices, caused a subprime mortgage crisis and ultimately ended in a nasty deleveraging process.

Economists generally agree that persistent giant trade imbalances reduce the global economy’s potential to return to a stable, healthy growth trajectory. And yet the intensely controversial nature of the issue and lack of obvious solutions have tended to divert policymakers’ attention onto other roads to recovery instead. In Europe, for example, the European Commission’s austerity mantra, alternately perceived by some as a panacea and others as a delusion, has dominated the recovery discourse in recent years to the detriment of other discussions. Debate has been far more heavily focused on debt and deficit levels rather than on current account balances, notwithstanding some encouragement of current-account deficit countries to boost their competitiveness and improve their external positions, as well as some finger-pointing at Germany for having arguably too large a current account surplus. A giant surplus in one country may be a positive sign of an efficient and competitive economy, yet it inevitably forces a deficit on others.

What, then, is the state of play with the world’s current account imbalances? Has the financial meltdown led to an incipient global rebalancing?

While the U.S. is set to retain its dubious title of the world’s current-account deficit giant for the foreseeable future, current account imbalances across countries have narrowed overall since their pre-crisis peak and the scales have shifted somewhat, albeit not yet enough. We assess here the changes underway in the three largest current-account surplus countries—Germany, China and Japan.

Germany

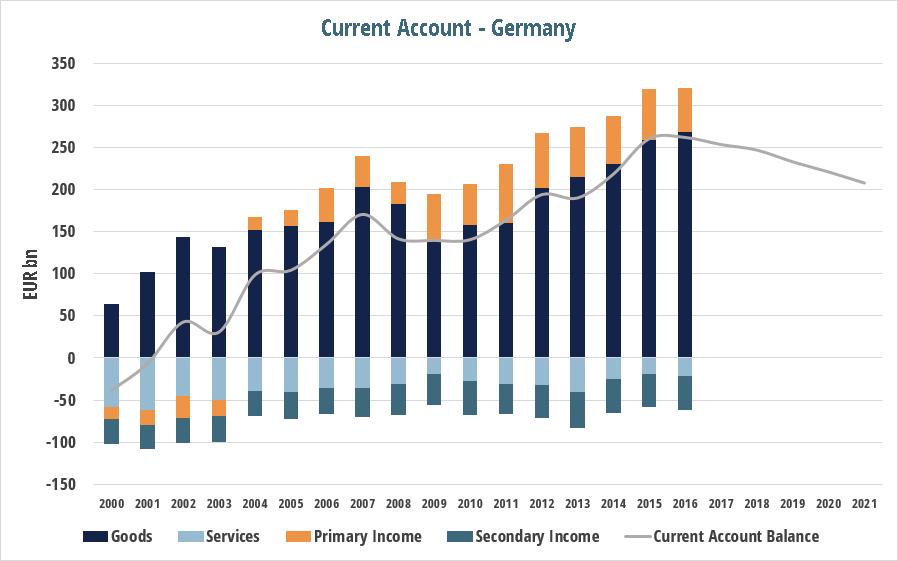

Sources: Deutsche Bundesbank (2000-2016 figures); FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast (2017-2021 projections)

Click on image to see a larger version

- Germany’s current account surplus surged to EUR 261bn (8.4% of GDP) in 2016, exceeding even that of China, the world’s traditional current account giant.

- We see the surplus moderating gradually from this year onwards but remaining high.

- Our Consensus Forecast projects that the country’s current account surplus will decline to EUR 207bn (5.6% of GDP) by 2021.

- Germany’s surplus has long resulted mainly from a robust goods export sector stemming from high productivity, low unit labor costs and strengths in creating high-tech products (including cars, its number one export), combined with comparatively weak domestic demand.

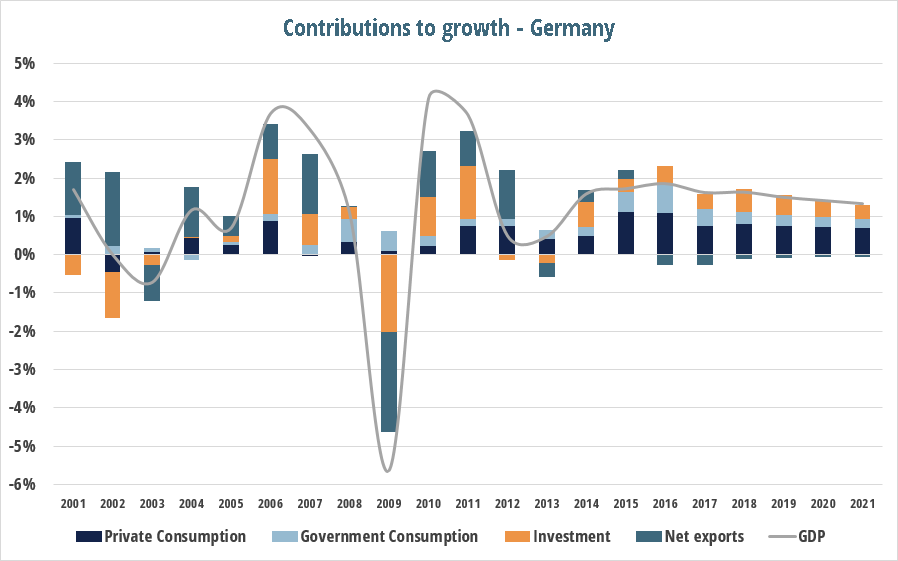

Sources: Federal Statistics Office, Germany (2000-2016 figures); FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast (2017-2021 projections)

Click on image to see a larger version

- Exports are not only the main component of Germany’s current account surplus, but also a longstanding driver of its growth engine.

- Our Consensus Forecast sees growth in exports picking up this year to 3.5% (2016: 2.6%) and achieving robust rates of at least 3.2% every year thereafter over our five-year forecast horizon. And yet stronger growth in imports will more than offset growth in exports, preventing the net external sector overall from contributing to growth.

- Domestic demand, which is traditionally weak in Germany, will decelerate and thus fail to pick up the slack, resulting in an overall deceleration in GDP growth.

China

Sources: State Administration of Foreign Exchange, China (2000-2016 figures); FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast (2017-2021 projections)

Click on image to see a larger version

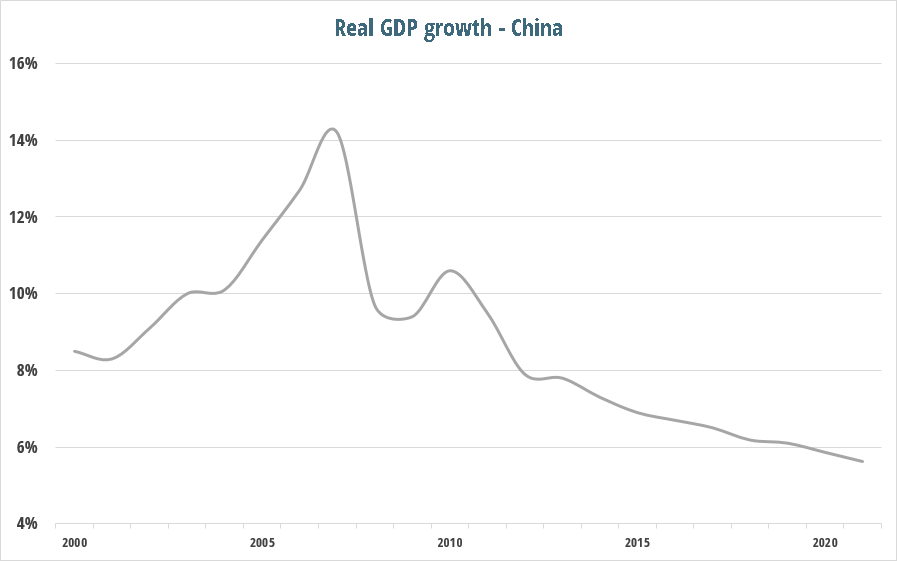

- After surging in 2005-2007, China’s current account surplus declined rapidly in the aftermath of the global financial crisis. Given the country’s massive GDP growth, the decline is most visible as a percentage of GDP. The surplus was 1.9% of GDP last year, down hugely from 9.9% in 2007.

- China’s current account surplus burgeoned in the pre-crisis years thanks to its booming goods export sector in the wake of China’s WTO accession in 2001, just as domestic consumption remained feeble since Chinese households favored saving over spending.

- Our Consensus Forecast sees the current account balance declining as a percentage of GDP over our five-year forecast horizon, to 1.4% (USD 226bn) in 2021.

- Although weighed down by the services deficit, the contribution of trade in goods to the current account has been picking up again in recent years. This, combined with the gradual depreciation of the yuan, has added fodder to President Trump’s revival of the United States’ traditional accusations against China of currency manipulation.

Click on image to see a larger version

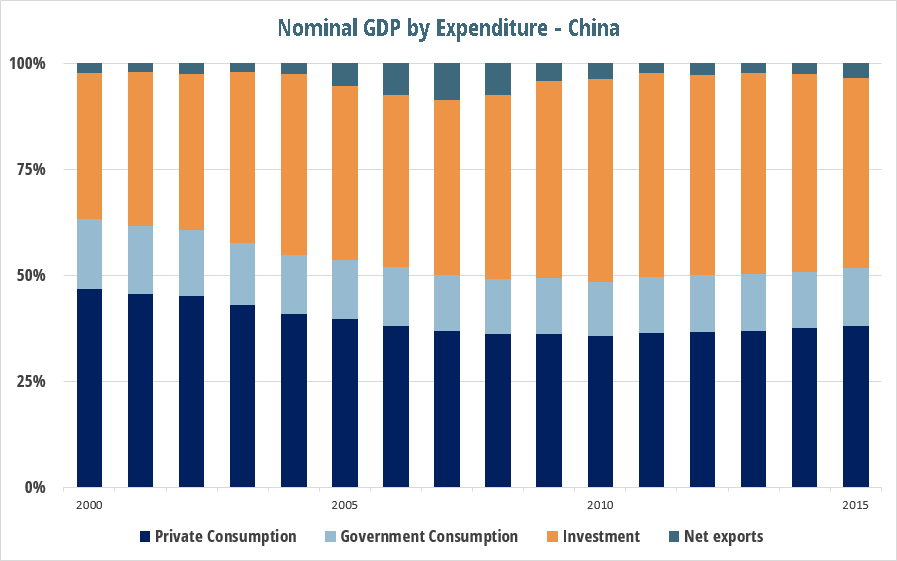

Sources: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2000-2016 figures); FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast (2017-2021 projections)

Note: Nominal GDP by expenditure is used to give an indication of the magnitude of different GDP components since the Chinese authorities do not provide a breakdown of real GDP.

Click on image to see a larger version

- China has long relied very heavily on an investment-led growth model to fuel its astoundingly high GDP growth in the years, pumping never-ending streams of money into state-owned companies. In the aftermath of the global financial crisis, it boosted investment even more to keep growth going.

- Despite such high investment, domestic demand has remained relatively weak due in significant part to high savings rates. Aware that such a growth model is not sustainable forever, the Chinese government has been seeking to boost consumption and services as it targets slower but more sustainable rates of economic expansion, with its 6.5% GDP growth target for this year matching our Consensus Forecast.

- If successful, strengthening private consumption should, in turn, have some consequences for the country’s current account balance too. For example, a boost in imports if Chinese citizens spend more should lead to a gradual decline in the current account surplus.

Japan

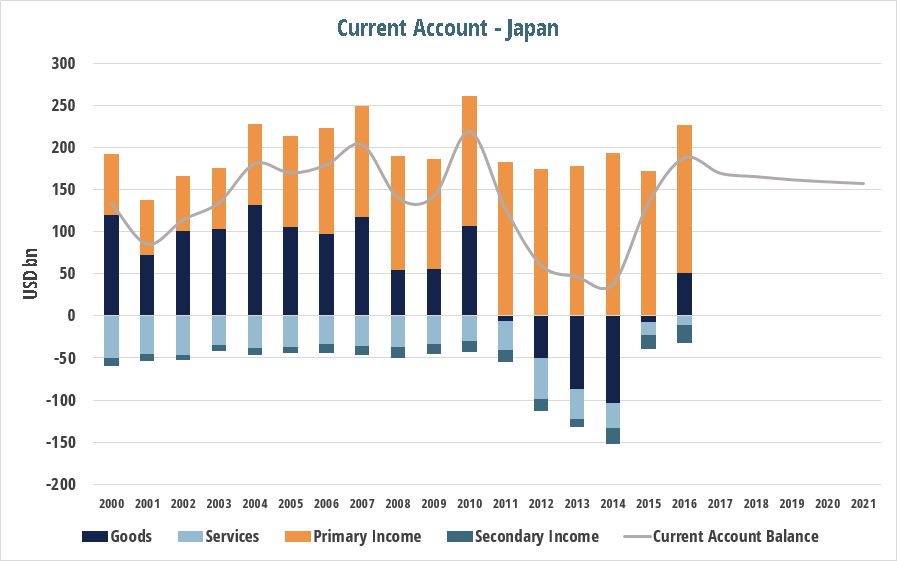

Sources: Bank of Japan/Ministry of Finance, Japan (2000-2016 figures); FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast (2017-2021 projections)

Click on image to see a larger version

- Unlike Germany and China, primary income rather than goods exports have been the main component of Japan’s current account surplus in recent years.

- This income mainly comprises interest earned on Japan’s extensive foreign assets, as well as dividends received by successful Japanese companies (e.g. car makers) from their overseas subsidiaries.

- After the Fukushima nuclear disaster of 2011, net foreign income alone kept the current account in surplus. The once strong trade balance fell into deficit as Japan became dependent on oil and natural gas imports. The improvement in Japan’s overall trade balance last year stemmed from falling imports due to the sharp drop in oil and natural gas prices, rather than improving exports.

- The evolution of the country’s current account surplus will depend to a significant extent on the evolution of oil and natural gas prices. Both are forecast to increase over the coming years, which will weigh on Japan’s goods trade balance and reduce slightly its current account surplus.

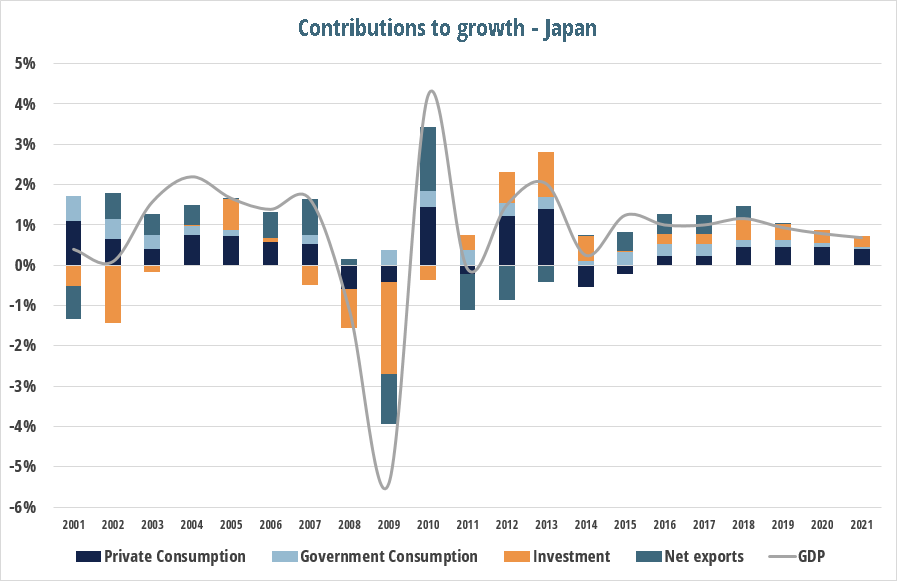

Sources: Cabinet Office, Japan (2000-2016 figures); FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast (2017-2021 projections)

Click on image to see a larger version

- Our Consensus Forecast sees GDP growth broadly stable this year at 1.1% (2016: 1.0%) before gradually decelerating over the coming years to 0.6% in 2021.

- So far this year, a relatively weak yen and strong global demand have been fueling activity in the all-important external sector. We see the yen appreciating slightly over the coming years at the same time as the country’s leadership in cutting-edge technology faces growing competition, which will put some pressure on exports.

- Just as increasing oil and natural gas prices will cause rising imports to pull down Japan’s current account surplus, they will also contribute to a deceleration in GDP growth—along with domestic factors such as weak private consumption—by reducing the contribution of the external sector.

- Rising trade protectionist policies and a sharp slowdown in China pose the main risks to Japan’s growth outlook.

|

Do you want to know more? FREE white paper: Is the Global Economy Rebalancing? In addition to the post above, you’ll get an in-depth look at Just click on the button below to download the white paper for FREE. |

Author: Caroline Gray, PhD, Senior Economics Editor