The book was published in 1845, with the UK in the grips of a frenzy which saw investors tripping over each other to pile into railway shares, bewitched by promises of a revolutionary mode of transport, a huge untapped market and spectacular profit growth. Even the likes of Charles Darwin and the Brontë sisters were swept up by the hype. Private firms hatched grandiose investment plans, submitted hundreds of bills to parliament for new railway lines, and saw their share prices roughly double in the space of a few years. Government was obliging; in 1845, it authorized around 3,000 miles of track, roughly as much as the previous 15 years combined. And at its peak, railway investment—which lagged a few years behind planning applications—surged to 7% of GDP, representing half of total investment in the economy at the time.

The phenomenon may have been highly localized, but it shares uncanny similarities to other bubbles which have cropped up time after time in the succeeding centuries: irrational exuberance among investors, a gradual shift into the mainstream of what was a hitherto niche pursuit, and inflated claims by firms—to name a few.

The Birth of the Bubble

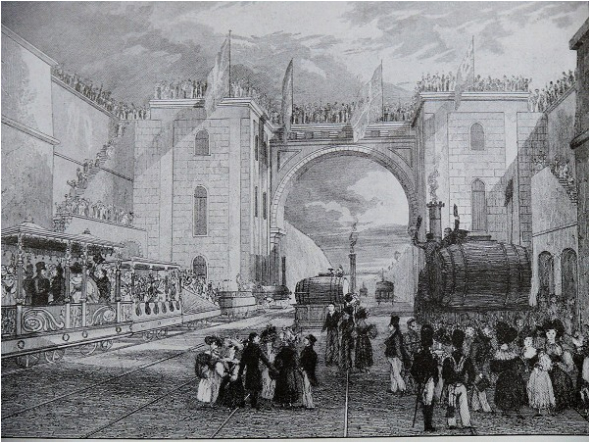

The seeds of the boom were sown more than a decade earlier, with the opening in 1830 of the world’s first commercial passenger railway line between Liverpool and Manchester, two burgeoning cities of the new industrial age. The UK was at the time fast becoming the world’s preeminent manufacturing powerhouse, and railways promised to catalyze the revolution underway, making it possible to move vast quantities of raw materials and finished goods more cheaply and quickly than ever before.

Until then, few people had considered the possibility of using trains to transport passengers. Many investors were actively opposed, arguing it would be all but impossible to encourage people to swap horse-drawn coaches for such noisy and potentially dangerous newfangled contraptions. However, against expectations, the Liverpool-Manchester line was a roaring success. Rail passengers far outnumbered coach travelers who had formerly used the same route; at the same time, the railway became wildly profitable, and investors were showered with dividend payments.

Investors now had hard proof that passenger railways could be money-making machines. However, although there was a spike in interest in rail shares in the mid-1830s, it was only several years later that Railway Mania truly took hold. This was partly because the Bank of England cut rates in the early 1840s, lowering financing costs and creating fertile ground for the bubble to come. But it was also because stocks could be purchased with just a 10% deposit, massively expanding the investor base. In this regard, there are glaring similarities with the 1920s U.S. stock market boom, which saw the emergence of millions of middle-class shareholders who bought stocks “on margin”. Parallels can also be drawn with the early 2000s subprime mortgage crisis in the U.S.; a combination of the Federal Reserve’s loose monetary stance and low down payments saw scores of Americans with dubious credit records get a tenuous toehold on the housing ladder.

Freewheeling Capitalism

With railway stocks now tantalizingly within reach of Britain’s emerging middle class, companies pulled out all the stops to market themselves to investors. Railway firms aggressively pushed their own shares—particularly in newspapers, the new media of the age. In late 1845, railway ads covered over half the space in many papers. Such ads were awash with inflated claims, optimistic revenue projections and questionable accounting practices, whipping up euphoria among investors.

What’s more, the accountancy profession was in its infancy; the government set no nationwide accounting standards, and the first professional accounting bodies would not appear for another few decades. Independent auditing was not a widespread practice; William Deloitte, the father of the modern consultancy firm, carried out one of the very first such audits on the Great Western Railway as late as 1849, several years after the Mania had subsided. As such, information regarding company accounts and future business prospects was surrounded by a thick fog of uncertainty.

Some businessmen even engaged in downright deception. A prime example was George Hudson; the so-called railway king—who at his peak single-handedly controlled over 1,000 miles of track and became one of the wealthiest industrialists of the day—ran a Ponzi-like scheme, paying dividends out of company capital.

Accounting standards have improved immeasurably over the subsequent centuries. Nevertheless, huge scandals continue to emerge today even in developed economies, with firms and governments engaged in a constant game of regulatory cat and mouse. Take the collapse of U.S. energy giant Enron in the early 2000s, which made skillful use of mark-to-market accounting to inflate profits, and special purpose vehicles (SPVs) to shield its mounting debt pile from prying public eyes. In response, governments around the world overhauled their legal frameworks. But the scandals keep coming. One of the more recent is UK construction company Carillion, which has been roundly criticized for failing to impair goodwill on its balance sheet, even when the underlying assets had fallen in value.

However, perhaps the most analogous situation of all is the telecoms bubble of the late 1990s. Drunk on the prospect of a disruptive new technology—and in some cases aided by financial trickery—U.S. telecommunications providers bet heavily on IT equipment, laying thousands of miles of fiber-optic cable and racking up whopping debts in the process. Investors eagerly jumped on board, and telecoms shares soared. However, around the same time as the Dot Com crash, the bubble burst, share prices tumbled, and many companies—including heavyweights such as Global Crossing, Worldcom and 360networks—went bankrupt.

The Role of the State

Private companies, however, were not the only ones responsible for the railway bubble; the finger of blame should also be pointed at the British government. The regulatory approach was lackadaisical to say the least, with parliament limiting itself to approving the construction of new lines and making no initial attempt to develop a coherent national rail strategy, or to put a brake on the huge proliferation of rail firms. Fragmented decision-making didn’t help either. At the height of the boom in 1845, there were 44 separate parliamentary committees analyzing potential network expansions, each focusing on a specific region of the country. Every single committee, without exception, approved at least one project.

The idea of too many regulators spoiling the broth should sound familiar. Just think of the UK before the 2008 financial crisis, when responsibility for financial stability was divvied up between the Bank of England, the Treasury and the Financial Services Authority. Or the EU, which created the European Banking Authority in 2011 in a bid to improve the oversight of the bloc’s financial institutions and reduce systemic risk.

But even the most joined-up thinking in the world would not have stopped the railway bubble, for the simple reason that many MPs also had skin in the game. Around 100 of the so-called “Railway Interest”, were said to have been actively involved in the industry. Their influence was brought into sharp relief in 1844, when parliament introduced a bill permitting the nationalization of railway assets at an attractive price. Companies were incandescent. After a period of heavy lobbying, the government buckled; the proposals were watered down, and ended up doing little to stifle market euphoria.

Parallels with the “Great Moderation” in the early 2000s are hard to ignore, although regulatory capture in this instance was far subtler. Then, public agencies and large financial corporations enjoyed a cozy relationship. Governments throughout the West practiced light-touch regulation, and happily collected tax receipts from booming banking sectors. Meanwhile, U.S. regulatory authorities were asleep at the wheel, blissfully unaware of the buildup of toxic assets in the housing sector.

A Lasting Legacy

In the case of Railway Mania, the bursting of the bubble brought economic pain for some; Investors who had bought at the crest of the wave were hit hard. But there was also a lasting legacy. By 1850, the UK boasted a 6,000-mile, gleaming new rail network which formed the backbone of the country’s transportation system and turbocharged the industrial revolution. The subsequent decades saw Britain’s global economic hegemony scale new heights.

This marks a clear distinction with many other speculative bubbles throughout history, which arguably brought little in the way of economic progress—think of Tulip Mania in 17th-century Holland or the global Bitcoin craze in 2017. Far more homologous is the 1990s telecoms bubble. Yes, many firms went out of business and shareholders were left scarred. On the other hand, the world was bequeathed with a comprehensive fiber-optic cable network which catalyzed future development.

The mere fact that Railway Mania can be compared to so many subsequent speculative episodes with similar characteristics makes one thing abundantly clear: It is easy in hindsight to spot a bubble, but much harder to stop one occurring in the first place. Without effective regulation in place, history is condemned to repeat itself.

As the protagonist of How we got up the Glenmutchkin Railway, a railway owner, says: “Such is an accurate history of the Origin, Rise, Progress and Fall of the Direct Glenmutchkin Railway. It contains a deep moral, if anybody has sense enough to see it; if not, I have a new project in my eye for next session, of which timely notice shall be given.”

Further reading:

- Tulip Mania: When Tulips Cost As Much As Houses

- Is this the beginning of the end for Bitcoin?

- 21 experts tell us what the future looks like for cryptocurrencies and blockchain

- From Riches to Rags: Have Cryptocurrencies Crashed for Good?

- Unwinding Carillion’s collapse and its wider implications

Images courtesy of:

Sample Report

5-year economic forecasts on 30+ economic indicators for 127 countries & 30 commodities.