New models have evolved to finance this vast increase in spending and to ensure care reaches even the most isolated corners of society. The vast majority of developed countries now use general taxation or social insurance healthcare systems alongside complementary private insurance providers.

Private Insurance

The birth of near-universal healthcare is a recent phenomenon. But the desire to provide some form of collective security in the case of ill health has much deeper roots. Private insurance models are the oldest form of risk-pooling in healthcare. They can be traced back to the medieval guilds, and insurance schemes established by societies in Western Europe—such as Sweden—in the 18th and 19th centuries.

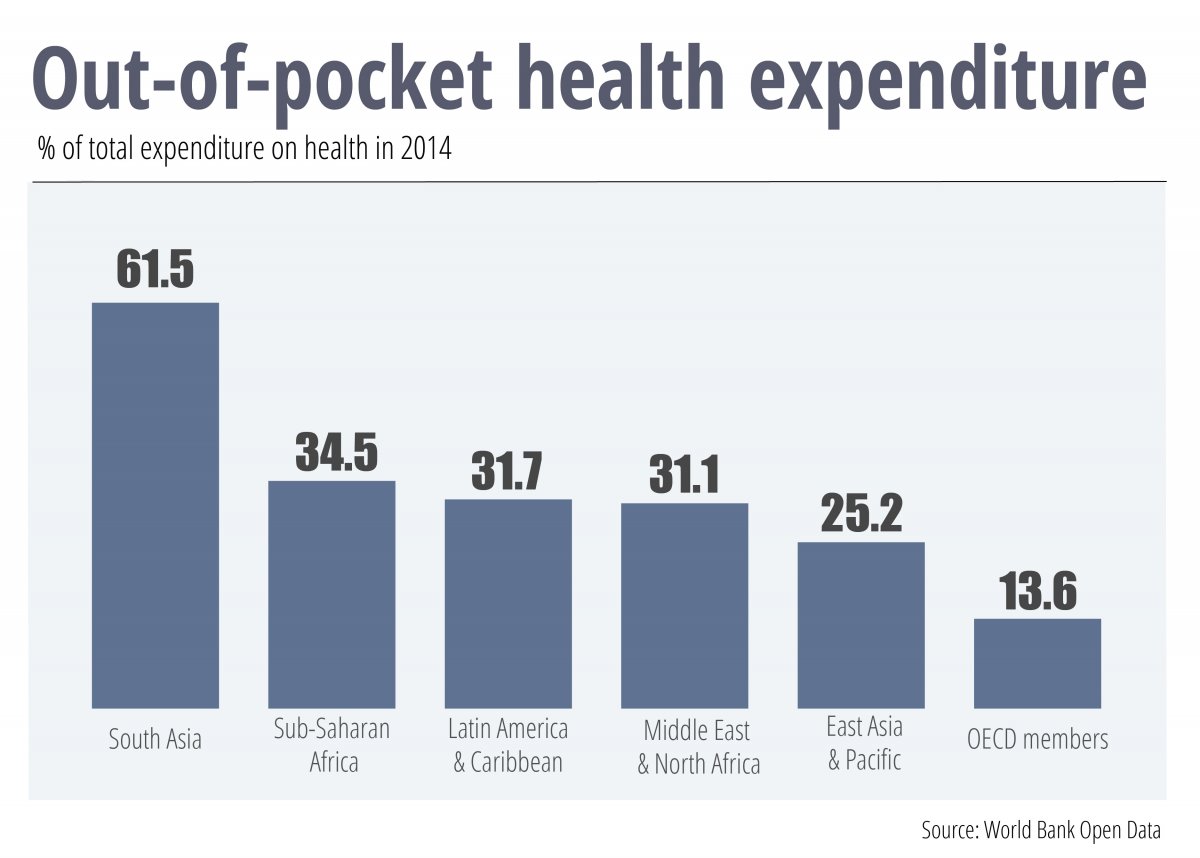

Today, private insurance schemes still play an important role in healthcare provision. This is particularly true in developing countries, where large informal sectors—and potentially inefficient tax administrations—make it tricky to generate sufficient revenue for public provision. In these nations, many citizens resort to out-of-pocket spending, which still accounts for over half of total healthcare expenditure in some parts of Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa. Private insurance improves on this predicament, by allowing citizens to better manage the risk of ill-health and leaving governments free to focus scarce resources on the neediest.

A similar argument is often made in many wealthy countries, where private insurance schemes tend to play second fiddle to comprehensive public healthcare systems. Governments have over the years dabbled with different financial incentives designed to shift patients to the private sector and relieve the burden on the public purse. For instance, Australia slaps a surcharge on high earners who do not take out a private health policy.

Proponents of a greater role for private insurance often repeat the claim that by encouraging competition, private provision is likely to boost efficiency, stimulate innovation and improve patient care.

But in reality, the private insurance market is likely to suffer from several types of market failure. Doctors may be tempted to overprescribe medication, safe in the knowledge that the insurer will foot the bill. Individuals with health problems are the most likely to purchase coverage, raising premiums for other users. And private providers may be tempted to “cream skim”—to select the healthy and wealthy and exclude the rest—to reduce risk and fatten margins.

This phenomenon was evident in Chile, a testbed for neoliberal healthcare ideas under the Pinochet dictatorship in the 1980s. Research shows that Chilean private health insurance providers—known as ISAPREs—attracted a disproportionately large number of affluent young males. Women in their childbearing years were often forced to pay substantially more for health plans and were likely to have more limited coverage, while many underprivileged people were shut out of the market altogether.

Smart regulation can go some way in ironing out these failures. The purchase of private insurance can be made compulsory, with subsidies for low earners. Insurers can be obliged to cover those with pre-existing health conditions. And the government can set minimum benefits packages for consumers. Many of these measures are part and parcel of the highly regarded Swiss healthcare system and bear strong similarities to the Obamacare reforms introduced in the U.S. in 2010.

Social Insurance

Over the years, many private insurance schemes have gradually mutated towards a more centralized, state-administered social insurance system. Germany was a pioneer in this regard; as early as the 1880s, then-Chancellor Von Bismarck succeeded in sewing together myriad sickness funds into a unified entity.

Widespread in continental Europe, the specificities of social insurance systems vary from country to country, but all share common characteristics. Funding comes largely from payroll taxes on firms and individuals, coverage tends to be mandatory—with citizens joining one of several competing funds—and health costs are at least partially reimbursed. In principle, only employed people have a stake in the system, so governments support the jobless to ensure universal coverage. Many opt for complementary private insurance to top up reimbursements; this is the case in France and Belgium, for instance.

Social insurance tends to foster greater equity than wholly-private systems, as coverage is virtually universal. And, specifically, earmarked levies ensure transparency and forward visibility of funding levels.

However, the model could render countries less competitive internationally, by driving up the tax wedge on labor income. In the OECD, social-insurance nations such as Belgium, the Netherlands, France and Austria have some of the highest taxes on labor. At over 50% of total labor costs, Belgium’s tax wedge is well over double New Zealand’s, where healthcare is financed from a far wider range of sources.

General Taxation

New Zealand is one of many countries which fund healthcare through general taxation, discarding the concept of insurance and severing the link between personal contributions and the level of service received. This approach is favoured in countries which have historically had a strong British influence, Scandinavia and Mediterranean nations like Italy and Spain. Funding sources vary; for instance, the UK and Spain lean more towards national taxes, while Sweden has a penchant for more local levies.

A major advantage of this model—at least in theory—is that it should cut administrative costs. Housing the entire healthcare system under one roof eliminates bureaucratic duplications and generates economies of scale. Axing insurance should streamline the back office, as no one needs to be employed to assess risk or calculate plans and premiums.

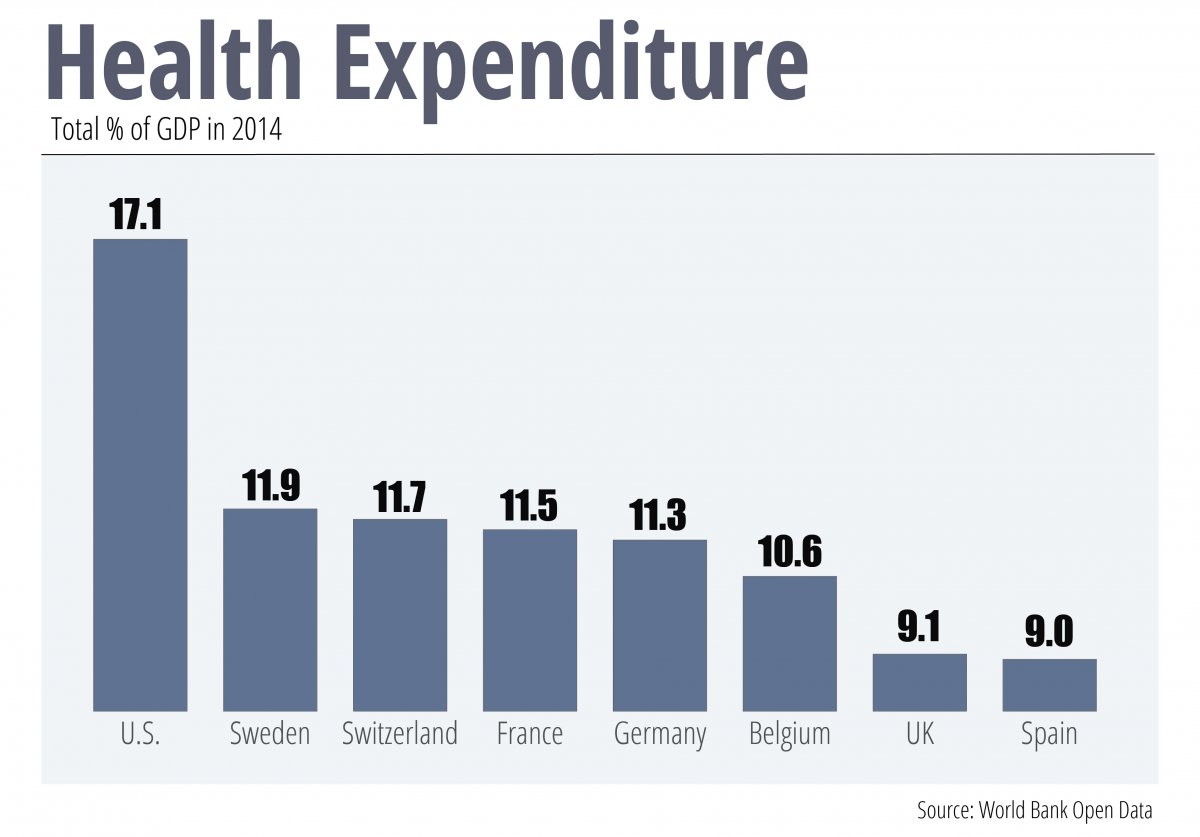

The case of the U.S highlights how costly a highly fragmented system of insurance providers can be relative to general taxation models. American insurance and billing related costs run into the hundreds of billions of dollars. And the country dedicates around 17% of GDP to healthcare, over double the OECD average. Only the Marshall Islands—a geographically isolated nation of sparsely populated islets and atolls which complicate social service provision—is as profligate.

Greater efficiency is far from guaranteed, however. Tax-funded healthcare systems reflect the wider public sector. Any graft, poor decision-making or mismanagement present in general government will likely manifest itself in the way the healthcare system is run, too.

Proponents of general taxation laud the constant standard of care across the board, regardless of a person’s position on the socioeconomic ladder. However, general-taxation funded healthcare is only as equitable and progressive as the tax system itself; in a hypothetical nation with flat-rate income tax where businesses did not pay a penny, it would be hard to argue that the poorest were getting a fair deal.

The general taxation model has the potential to be fair, but it can also be financially fragile. This is partly because raising taxes is unpopular and takes political mettle. Politicians could be tempted to duck tough decisions, even if the health service is crying out for extra cash.

It’s also because healthcare has to compete for funding with other government departments. This could bog down debates over health spending in a quagmire of political horse-trading, and cause funding to vary wildly depending on the government’s political stripes, hampering long-term thinking. Britain’s NHS is a prime example. Spending increases were contained during the Thatcher government of the 1980s. Then the Labour party took power at the turn of the 21st Century and opened the spending taps. Since the great recession, under Conservative leadership extra spending has turned from a flood to a trickle, with the government bent on driving down the deficit.

Earmarking taxes for investment specifically in the health service could smooth these spending fluctuations. This practice, known as hypothecation, has existed for decades in Australia, where tobacco tax revenues are ploughed back into healthcare. Finland, South Korea and Portugal have adopted similar schemes. In light of recent funding pressures and concerns that the NHS is under strain—evidenced by the latest winter crisis—many voices in the UK are calling for one too.

The country which typifies at once the very best and worst aspects of general taxation systems is Brazil. Founded in 1988, the country’s Unified Health System (Sistema Único de Saude, SAS) brought half of the population, then lacking health coverage, in from the cold. A further reform in 1996 led to decentralization, giving municipalities and states a greater role in running care and setting minimum investment targets. Tens of millions of poorer Brazilians benefit from the Family Health Program, consisting of around 30,000 teams of health workers who aim to reach even the most remote corners of the country. Since the public health service was established, life expectancy has risen from 65 to 75. Infant mortality has plummeted, and regional inequalities between the wealthy south and impoverished north have narrowed.

However, severe deficiencies remain. The SUS remains chronically underfunded, a situation which was made worse after the government scrapped an earmarked financial transaction tax in 2007. Equipment is outdated, waiting lengths are lengthy, and the system lacks staff. Recent data shows there are a mere 1.5 nurses per 1,000 people, compared to an OECD average of 8.8. It is little surprise that those who can afford to jump ship; around a quarter of Brazilians have taken out private insurance.

The Verdict

When examining private insurance, social insurance and general taxation models, available research tends to suggest that none systematically outperforms the rest. Given the substantial costs and upheaval associated with changing systems, this is just as well. In fact, there is often more variation within groups than across them—just compare the health outcomes of private-insurance based Switzerland and the U.S. Using life expectancy as a crude measure of a health system’s effectiveness, the most longevous nations are an eclectic mix of all three systems.

The healthcare system a country eventually plumps for is a result of myriad intertwining cultural and historical factors. But the challenges facing all healthcare systems around the world are identical. New treatments are growing costlier. Obesity levels are soaring. And in large part as a direct consequence of the effectiveness of modern healthcare, populations are ageing rapidly, bringing more complex and chronic conditions.

Novel solutions will be needed to tackle these issues. Improving prevention and encouraging healthy lifestyle choices will be key, as will grappling with mental health problems and strengthening coordination between health and social care. And, inevitably, somewhere down the road healthcare systems will require extra funding. Governments will have to bite the bullet and be frank with citizens that maintaining current service levels will come at a price.

When William Beveridge published his report all those decades ago, little could he have imagined the strides which have since been made in improving access to quality healthcare across the globe. Neither could he have envisaged how health would gobble up ever more public resources, or the conundrums facing governments and experts the world over regarding the future sustainability of health services. But one thing is unchanged. Societies’ battle to eradicate Beveridge’s Five Giants remains as fierce as ever.

Sample Report

5-year economic forecasts on 30+ economic indicators for 127 countries & 33 commodities.