Thursday 19 May was a dark day in Sri Lanka’s history, as the country defaulted on its debt for the first time ever. The country had fallen victim to tightening global financial conditions, rising currency outflows and a surge in import prices weighing on public coffers. Even before the war in Ukraine—which made external conditions much tougher—the country’s public debt levels were already unsustainable, reaching over 100% of GDP in 2021.

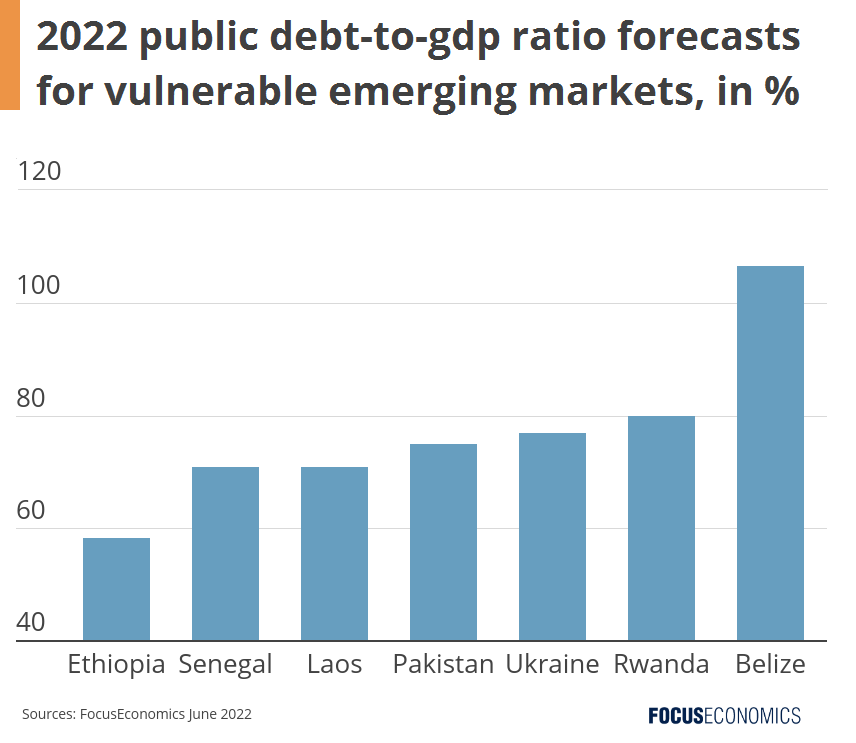

Sri Lanka’s sovereign default was the first this year. But it may by no means be the last, as aggressive monetary tightening by the Federal Reserve and other developed economies causes capital outflows from emerging markets. In a recent post, Marcello Estevão, a director at the World Bank, estimated up to a dozen countries could default over the next year. The most vulnerable economies are those dependent on imported food and fuel with pre-existing fiscal and current account imbalances, and high public debt denominated in foreign currency. Countries in conflict and/or subject to international sanctions, such as Russia and Ukraine, are also at risk of default.

Indeed, recent developments suggest fresh defaults could be imminent. In late May, the U.S. closed an avenue through which Russia is currently making international bond payments for instance, while in Pakistan, political infighting is bogging down negotiations for a much-needed IMF bailout. The consequences of default for emerging markets would be significant, as they would find themselves locked out of global capital markets, with funding for growth-enhancing investment drying up as a result.

Steps could be taken to ward off the threat of future crises. Crucially, developed nations could make it easier for poorer countries to restructure their debts, such as by enhancing the G20’s Common Framework for debt treatments. IMF support packages will also be vital. And working towards a peaceful solution to the conflict in Ukraine would remove a key source of global inflation, reducing emerging markets’ import bills and the rate of global monetary tightening. However, reforms to the Common Framework and conflict resolution will likely take time: Until they occur, more defaults are to be expected.

Insights from Analyst Network

Marcello Estevão, a global director at the World Bank, said:

“So far, just three countries have applied [to the G20’s Common Framework] and progress on restructuring their debts has been slow. That sends exactly the wrong signal to other countries with unsustainable debt, many of which have refrained from seeking the relief precisely because of the slow progress: they fear applying to the Common Framework would cut off their access to private capital without restoring the flow of bilateral credit.”

On Pakistan’s predicament, the EIU said:

“EIU believes that the government has limited options to shore up foreign-exchange reserves (which currently provide cover for less than four months of imports), barring the liquidity line from the IMF. The authorities will therefore be forced to enact unpopular austerity reforms over 2022. Some financial aid will be forthcoming in 2022-23 from China, Pakistan’s long-term ally, but that will have tougher attendant conditions and will not be enough to tide over near-term financial shortages.”