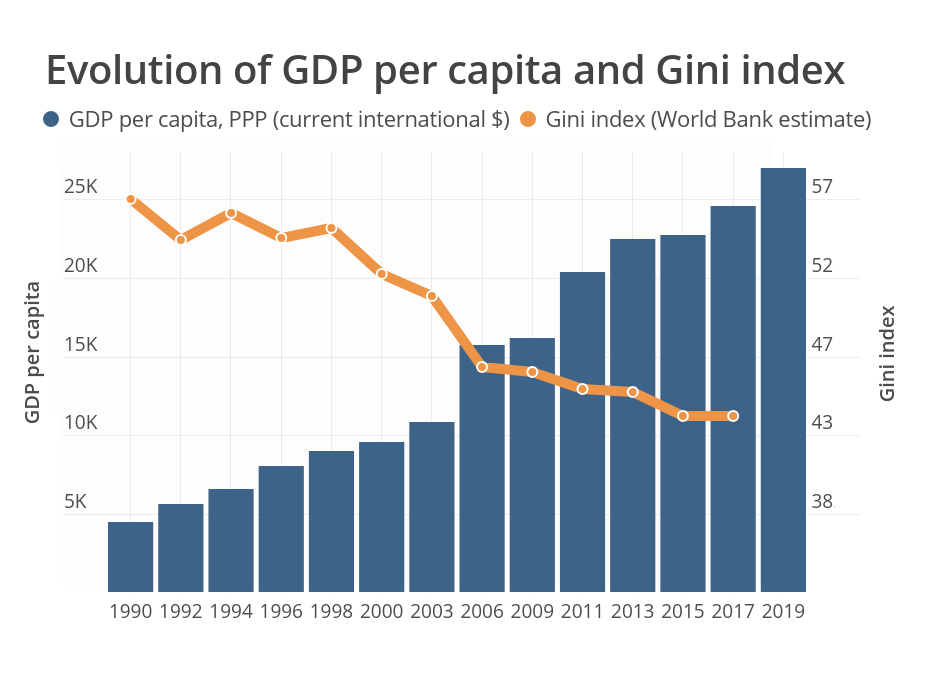

A few decades ago, looking east from the top of San Cristóbal Hill in the heart of Chile’s capital, Santiago, were a series of leafy, low-rise residential neighborhoods stretching out towards the foothills of the Andes. Today, however, an observer is greeted by the towering skyscrapers of the city’s “Sanhattan” financial district—including what was until recently Latin America’s tallest building, the Gran Torre Santiago—which stand as a striking testament to the transformation of Chile’s economy into one of the continent’s wealthiest in GDP per capita terms.

Much of this success rests on the policies of a series of pragmatic, centrist governments following the return of democracy in 1990, which softened the edges of the neoliberal model put in place under General Pinochet without sacrificing economic dynamism. Since then, mean years of schooling have risen from 8 years to 11, life expectancy has shot up from 74 years to 80 and the poverty ratio has fallen from over a third to under 10%.

This impressive development has come without racking up debt, in contrast to the country’s neighbors: The shrewd decision to channel tax windfalls from copper sales into a rainy-day fund, coupled with clear fiscal rules, left room for one of the largest stimulus packages in the region in the wake of the Covid-19 crisis. Moreover, Chile’s world-beating vaccination rollout this year owes much to the creation of a solid public healthcare network and an efficient bureaucracy.

But despite these achievements, dissatisfaction is rife over yawning income inequality—the gini coefficient is far above the rich country average—and the high cost of living. Citizens’ trust in institutions has been eroded. And anger at political elites runs deep.

These frustrations boiled over in late 2019 in a series of violent protests, which saw public buildings ransacked and the capital’s subway system firebombed, leading to the army being deployed on the streets. In response, the government took the radical step of holding a referendum on a new constitution—a vote which the yes campaign won by a landslide.

In May this year, a constituent assembly will be elected by popular vote to draw up the next carta magna, in what promises to be a fraught, lengthy affair. For the millions of Chileans who have taken to the streets in recent years to protest, enshrining new social rights into law will be key. But there are fears in some quarters that, spurred on by the current wave of populist, anti-government sentiment, the members of the assembly could sweep away the cornerstones of past economic success in the process.

In May this year, a constituent assembly will be elected by popular vote to draw up the next carta magna, in what promises to be a fraught, lengthy affair. For the millions of Chileans who have taken to the streets in recent years to protest, enshrining new social rights into law will be key. But there are fears in some quarters that, spurred on by the current wave of populist, anti-government sentiment, the members of the assembly could sweep away the cornerstones of past economic success in the process.

“The country is at a crossroads”, says Massimo Bassetti, senior Latin America economist at FocusEconomics. “The coming period will be decisive in setting out the country’s economic trajectory not just for the next few years, but for the next decades.”

- Minority rule

One key figure will define the outcome of the constituent process: two thirds. This is the majority needed for approval of the new constitution, and the fact that the right-of-center parties are running in the elections under a single ticket—unlike the more divided left—means they are likely to gain enough seats to form a blocking minority. This should force all parties to moderate their positions, and ensure that the basic tenets of the current model, such as an independent judiciary and Central Bank, and respect for private property rights, remain in place.

“Voters will opt for enough pragmatic representatives to the constituent assembly to prevent radical proposals from being adopted”, state analysts at the EIU.

However, at the same time this raises the risk of a constitution which feels like a carbon copy of its predecessor, or—worse yet—failure to reach an agreement at all. Either scenario could fritter away what little goodwill remains towards the political class and spur renewed social unrest.

A fragmented assembly could also stymy efforts to build on the current charter in areas where there is room for improvement. The country’s institutional architecture for instance is widely regarded as in need of an overhaul, with recent years seeing entrenched political deadlock between successive presidents and a Congress outside their control. Piñera’s flagship pension reform is a case in point: First presented in 2018, the bill has floundered, while parliament has since approved measures allowing for the early drawdown of retirement pots despite fierce opposition from the executive.

Given overwhelming public pressure, a deal is still the most likely outcome. And it seems clear that the new text will move the country more towards a social-democratic economic model—although whether any new social rights enshrined in the document are largely symbolic, or instead set legally binding obligations for future governments, remains to be seen.

- Charting a new course

In any case, a new constitution alone will not cure Chile’s ills. That will be a job for the victor of this year’s presidential election, via the passage of concrete reforms in Congress. The outcome of the vote is still highly uncertain, with many candidates yet to be formerly chosen. But the two-round nature of the contest, against the backdrop of an economy which should be recovering strongly, limits the likelihood of a fringe candidate getting in.

“We also anticipate that a moderate candidate will win the presidential election, as opinion polls suggest a greater preference for moderates over extreme candidates,” argue analysts at the EIU. “However, this will happen in a second-round vote (scheduled in December), as risk-averse voters will opt to coalesce around the moderate ticket. A risk to this forecast stems from the possibility that public opinion on pragmatic policies sours amid what we expect will be a contested constitutional rewrite and a potentially divisive presidential campaign.”

The next president will face the tricky task of tackling the root causes of social discontent and increasing the role of the state, while simultaneously retaining Chile’s prized reputation for fiscal prudence—all within the framework of a political system which could be just as inoperative as it is today. While Chile’s fiscal position remains healthy—net public debt is still low by emerging-market standards—failure to quickly establish a credible plan to get the public debt-to-GDP ratio on a downward path would likely further erode the country’s credit rating, which has already taken a hit this year due to the pandemic.

According to economists at Fitch Ratings: “Over the medium-term, significant spending pressures are likely to persist, and the Congress could push more public spending that could impede faster fiscal consolidation, even if tax reforms are passed to increase revenues. The rewriting of the constitution could create social mandates that place additional burden on public finances as well.”

For now, economic prospects are fairly upbeat: The rapid pace of inoculations and ample stimulus measures should support one of the strongest recoveries in Latin America this year, helping to narrow the fiscal deficit in the process. But the longer-term outlook hinges on the type of society that emerges from the current period of political flux.

Back in Santiago, the district of Sanhattan may be an undisputed sign of the country’s development progress. But for many of the ordinary Chileans who crane their necks to gaze up at the gleaming office blocks all around, the area exemplifies the flaws in the current economic model: An excessive concentration of wealth—both geographically and in populational terms—and of an out-of-touch elite who live detached from reality in the safety of their ivory towers. Changing this highly ingrained image for one of an inclusive economy which offers opportunities to all will be the key challenge in the years to come.