To stand inside Manchester’s Liverpool Road Railway Station in 1830, soon after it opened its doors to the public, was to witness the dawn of a new age in transport. The station marked the Manchester terminus of the world’s first inter-city passenger railway service, linking Lancashire to the port town of Liverpool. With a top speed of just 36 mph, trains stopping at the station were slow by today’s standards. Standardized railway time had yet to be introduced, so clocks on the platform in Manchester ran a few minutes ahead of those in Liverpool, causing headaches for travellers. But despite these shortcomings, the station and the train line which served it showcased the north of England in the technological vanguard, and were powerful symbols of the region’s economic and industrial prowess.

The inauguration of Liverpool Road acted as a catalyst for a veritable metamorphosis of the UK’s physical and economic geography. Railway lines soon sprouted up across the north, forming the backbone of the industrial revolution as they ferried raw materials to factories and transported manufactured goods back to ports for export. As a result, international markets were flooded with British wares. The advent of the railways also helped northern cities bloom into global powerhouses, shifting the balance of economic power in the UK away from London and the South East. Manchester became “Cottonopolis”, a worldwide center for the cotton industry, while Leeds developed strengths in engineering, chemicals and textiles. Newcastle became a crucial nucleus for train and ship building.

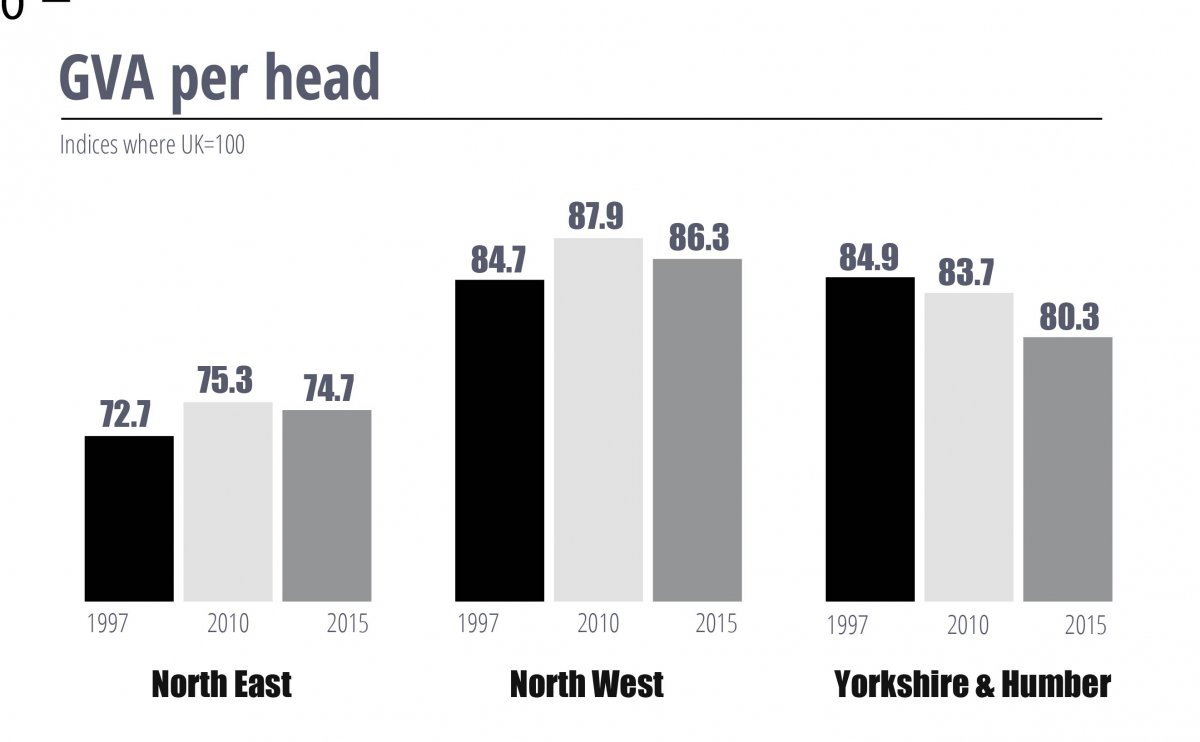

And so, the Liverpool Road Railway Station—which has today been converted into the Museum of Science and Industry—was an auspicious place for then Chancellor George Osborne to deliver a speech three years ago aimed at introducing an initiative he hoped would launch a second economic revolution in the north. The plan, baptised the Northern Powerhouse project, would help northern regions close the economic gap with southern regions, and act as a counterweight to the dominance of the capital region. The rationale behind such a project was clear: The north’s economy has struggled to reinvent itself since the decline of heavy industry in the second half of the twentieth century. By 1997, GVA per capita in the North East, North West and Yorkshire and Humber regions was around 20% below the country average.

In a bid to revive the area, the Labour administration, which came to power that year, ploughed significant sums into urban regeneration schemes. Northern cities got gleaming new industrial estates, shopping centres and cultural venues. City centers were spruced up. Abandoned warehouses and factories were converted into swanky apartment blocks. A renewed sense of civic pride took root in the great northern capitals, which was on boisterous display at the Manchester Commonwealth Games in 2002.

The Labour government’s efforts to boost the north’s economy were only partially successful, however. By 2010, the North East and North West enjoyed only a slight convergence in GVA per head with the national average, while Yorkshire and Humber had slipped further behind. The north remained over reliant on the government for wealth creation: The percentage of public-sector employment was higher than in any other English region. This left the northern economy acutely vulnerable to the government spending cuts enacted from 2010 onwards under the Coalition government, which dragged on the region’s economic performance. Indeed, economic growth in the three northern regions averaged a mere 2.0% in the 2010–2015 period, below the UK average of 2.5%.

The Vision

When Chancellor George Osborne stepped out on stage on a bright June morning in 2014 in the Power Hall of Manchester’s Museum of Science and Technology to present his vision for a Northern Powerhouse, he spoke surrounded by huge steam engines and turbines. These relics of the city’s illustrious past served as a fitting metaphor for the enormity of the transformation he wished to set in motion. “The cities of the north are individually strong, but collectively not strong enough,” he began. “The whole is less than the sum of its parts.”

In the modern world, he argued, powerful economic agglomeration effects were inexorably sucking economic activity into large urban areas. Businesses were flocking to big cities in order to access pools of skilled labour, forming industrial clusters. These cities consequently benefitted from greater innovation and specialization, and were more productive as a result. While London increasingly dominated the country’s economic landscape, the north was being left behind in the global innovation and technological race. “We need to bring the cities of the north together as a team,” he said.

To achieve this aim, the former Chancellor set out several policy areas, including first and foremost transport. The north’s transport network is dated; congestion along key roads such as the M62 motorway is chronic, and trains are overcrowded and slow. Commuters in the southern town of Reading can cover the 40-mile journey to the heart of London in a mere 26 minutes by train. For those in the north, making a similarly long trip between Manchester and Leeds takes roughly twice as long.

Osborne pointed to a smattering of policy pledges designed to modernize the north’s dated infrastructure. These included a GBP 600 million commitment proffered by the Treasury to finance the Northern Hub project, which would cut journey times and improve train frequencies across the region. The Metrolink tram network in Manchester was extended, and the government pledged to spend billions on the HS2 high-speed rail network, which would link key northern cities to the capital by the early 2030s, supporting thousands of jobs. The end goal was to make travelling in the north “the equivalent of travelling around a single global city”.

While attempting to bind northern cities more closely together economically, George Osborne spoke of a desire for greater political separation between them and Westminster—a “serious devolution of powers” modelled on the devolution process undergone in the capital that would give northern city councils greater control over local decisions. Giving local leaders increased control would provide northern cities with a louder voice on the national stage, it was argued. If greater decentralization led to more targeted and efficient policy making, this would boost the north’s economy. Although regional autonomy has long been commonplace in many European countries, it is a departure from the norm in a country like the UK, which has a strong centralized government.

Nestled among concrete measures on transport and devolution were vaguer utterances regarding science, innovation and the creative industries. “We want to see science here turned into products here—and into jobs and growth here,” Osborne declared, in reference to the assertion that British universities struggle to commercialize world-class research. In order to help northern economies thrive, he spoke of the importance of “backing their creative clusters”.

This latter commitment is particularly vital. Fostering creative industries in the north is not merely a way of boosting the region’s economy today. It could also be a way of future-proofing employment prospects. Research by innovation foundation Nesta has found that jobs in the sector are three times less likely to become automated in the coming decades than those in the rest of the workforce. The foundation also revealed that creative hubs are disproportionately present in London and the South East, with the capital alone accounting for four in ten creative sector jobs. The North East, in contrast, is home to a mere 2%.

The Impact

More than three years later, signs of progress are palpable, though much remains to be done. According to Dr. Dean Garratt, a researcher at the Nottingham Business School, the creation of a project targeted specifically at the north has focused minds: “The real positive is that it has […] streamlined decision-making and hence given an impetus to getting things done”.

This is most evident in terms of regional autonomy, an area where Manchester has been a trailblazer. The Greater Manchester Combined Authority (GMCA), formed in 2011 as the amalgamation of smaller councils, has obtained the farthest reaching devolution deal of any northern region. Through a combination of technical competence and savvy negotiating, the city has wrested greater autonomy over housing and transport from Westminster, and is currently piloting the retention of 100% of locally-collected business rates to boost regional investment. A milestone was achieved in 2016, when the GMCA became the first English region to be granted full control of its GBP 6 billion health and social care budget.

Other northern cities have belatedly followed suit. In May 2017, the Liverpool City Region and the Tees Valley joined Manchester in electing “metro mayors” who have responsibility over areas such as transport and planning. “Devolution Deals are a good framework,” says Chris Richards, Head of Business Environment Policy at EEF, “and the Government should double down and finish the job in getting Deals rolled out to all areas. They can achieve this by publishing what is on offer for local areas rather than continuing the game of negotiation hide and seek.”

This highlights some of the criticisms commonly levelled at the government’s devolution strategy: Deals are conducted on an ad-hoc basis, the remits of metro mayors vary wildly from city to city and progress has been uneven. For instance, the Leeds City Region has a population similar to that of Greater Manchester, but has so far failed to strike a meaningful accord with Westminster. Infighting among local leaders is also holding back progress: In mid-September, the devolution agreement for the Sheffield City Region was dealt a crushing blow after two councils withdrew their support.

Regarding transport, changes have been even patchier. Some key projects, such as the Mersey Gateway Bridge, the expansion of Manchester airport and the Northern Hub, are underway. A new pan-north strategic transport body, Transport for the North, has been created. If it is granted statutory status this year as hoped, it would become the first sub-national transport body in England, unifying transport planning across the region. Research by the Progressive Policy Think Tank (IPPR) shows that the North West has secured GBP 680 per head of transport spending commitments for the coming years, the highest of any region outside London. According to the IPPR, this is a sign of the North West “catching up” with the capital.

However, Mr. Richards argues that a blinkered focus on trying to level out transport spending across the country is the wrong approach. “The key is to kick start agglomeration, not look to match pound for pound infrastructure investment across areas. As a result, this should not just be about everywhere getting a big project, some of the major improvements in transport in London early on were low-capital intensive schemes such as the expansion of the bus network, the introduction of a congestion charging scheme and the rollout of a smart ticketing system.”

In terms of improving connectivity within cities, the north still has work to do. A recent report by the Centre for Cities highlighted that productivity in northern cities was flagging, partly because of poor inter-city connections. “Strengthening transport networks within northern cities is a bigger priority than inter-city links,” read the report.

Questions have been raised in recent months over the government’s continued commitment to upgrading the north’s transport infrastructure. In July, Transport Secretary Chris Grayling cast doubt on the eventual electrification of the Leeds-Manchester railway line—previously deemed a key element of improving east-west links. Northern leaders were up in arms. In a joint communiqué, they called on the government to “clarify its position on both short-term and long-term commitments” and criticized the “considerable uncertainty” generated by the announcement.

The Transport Secretary’s statement feeds into the narrative that Theresa May’s government is generally lukewarm about the Northern Powerhouse. The initiative was George Osborne’s political pet project, but he left the cabinet following May’s appointment as Prime Minister in 2016. Jim O’Neill, the former Treasury Minister who was instrumental in drawing up devolution deals with northern cities, soon followed suit. The Chief Executive of Transport for the North and the government’s Northern Powerhouse minister also left their posts. These senior casualties have led to a loss of impetus; without strong support from the top levels of government, the project risks an early death.

Continued support from Westminster will also be pivotal when faced with the elephant in the room: Brexit. Financial aid from the European Regional Development Fund and the European Investment Bank, dubbed “Jeremie”, currently plays an important role in providing credit to thousands of northern businesses. Replacing this stimulus with British government funding post-divorce will be key to allowing the north’s private firms to flourish.

Encouraging signs of a strengthening of the region’s private sector have already emerged in recent years, with the technology sector a prime example. According to Tech North, a government agency set up to promote the northern technology ecosystem, investment in the industry has skyrocketed in the last three years, from a mere GDP 25.1 million in 2013 to GBP 201.2 million in 2016. Durham is now home to Atom Bank, a pioneering mobile banking company. Cheshire houses The Hut, a thriving e-commerce firm. Newcastle is a burgeoning computer gaming hub, with Ubisoft recently investing in new facilities there.

However, maintaining this momentum will require sustained improvements in human capital in the north, an area which the Northern Powerhouse project largely overlooks. In 2016, the Office for Standards in Education warned of a “growing north/south divide” in educational attainment, with the proportion of high-achieving primary school students going on to obtain top GCSE grades in the north and Midlands six percentage points lower than elsewhere in the country.

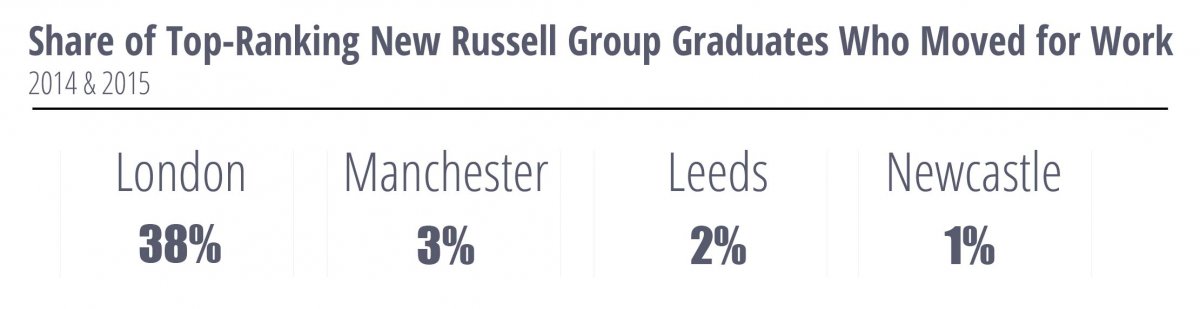

Keeping hold of the skilled workers the north does produce is no easy task either. London is a magnet for talent, bringing in the best and the brightest from around the country and draining the north of its most skilled workers. In 2014 and 2015, almost 40% of graduates with first or upper-second class degrees were working in the capital six months after finishing their studies. As a result, six out of ten Inner London residents are university graduates, roughly double the figure for the North East. Anecdotal evidence suggests some firms struggle to fill regional offices, despite the stratospheric cost of living in the capital.

According to one recent graduate of Oxford who is originally from the north and now works as a software developer in the capital: “A large part of it [the decision to move to London] was that most of my friends from university were going to be staying in the South […] There also seemed to be a higher concentration of the sort of jobs I was looking for.”

Dr. Garratt is downbeat regarding the eventual impact of the Northern Powerhouse initiative: “Long-term success is questionable given my doubts about how much additional money has really been behind this change in regional policy. In the longer term, even the impetus provided by the change in decision-making processes would be expected to wane.” Mr. Richards takes a more positive view. “The foundations for a turnaround are in place,” he says.

The UK economy as a whole is forecast to expand 1.5% on average over the next three years, according to the FocusEconomics panelists’ forecast. Will the Northern Powerhouse project be able to ensure that the north shares in this growth? To have any chance of lasting success, there needs to be firm political commitment, public policies targeted at boosting physical and human capital, and ample financial resources. Only then will the north be able to rise once more to the economic fore, just as it must have seemed to the passengers entering Liverpool Road station for the first time, nearly two centuries ago.