Click on the image above to open a larger version

In both countries, economic progress has started at the top. Ethiopia and Rwanda have arguably been bestowed with competent, technocratic leaders in recent decades, who have engaged in long-term development planning. Ethiopia is currently implementing its second Growth and Transformation Plan and aims to reach lower-middle income status by 2025. Meanwhile, Rwanda has drawn up a National Strategy for Transformation, as part of its overarching Vision 2050 initiative which sets an ambitious objective of transforming Rwanda into a high-income nation. As keen students of economic history, both governments are looking to emulate other recent success stories, particularly the vertiginous development observed in many East Asian economies.

The key pillar of these strategies is moving up the value chain. In Ethiopia, the government is largely pinning its hopes on the manufacturing sector, which by 2025 should account for 20% of GDP and 50% of exports. Around a dozen industrial parks have been built or are under construction, with a particular focus on light manufacturing, such as textiles and leather products. Meanwhile, the country has invested heavily in road and rail infrastructure to bring these future goods to market.

Rwanda has plumped for a slightly broader approach. Alongside manufacturing, the administration is betting heavily on the services sector. One ambition is to turn the country into a regional hub for conferences and events, and to this end the Kigali Convention Centre was unveiled in 2016 to the tune of USD 300 million—a significant outlay for what is still a very poor country. There is even an attempt to leapfrog straight to high value-added activities, as evidenced by attempts to create an innovation fund and establish an “innovation city” bringing together tech firms and leading universities.

On the demographic front, the wildly different populations of Ethiopia and Rwanda mask similar underlying trends. Both have seen fertility rates plummet in the last two decades, from between six and seven births per woman in the mid-1990s to roughly four today, thanks in no small degree to effective family planning policies. If the decline continues, they could be on course to reap the benefits of a demographic dividend in the coming decades, as the proportion of the working-age population swells.

Both countries have attracted the interest of international investors, particularly China—arguably Africa’s most important economic partner. This interest has been particularly evident in Ethiopia over the last decade, where Chinese capital has poured into infrastructure projects—most notably the Addis Ababa-Djibouti railway, which gives landlocked Ethiopia access to the sea.

Rwanda has taken longer to catch the Asian behemoth’s eye, but is quickly making up for lost time. Chinese President Xi Jinping made his first state visit to the country in July 2018, during which Rwanda signed up to the Belt and Road Initiative, the Chinese-funded series of infrastructure projects throughout Africa and Asia designed to boost regional connectivity. Rwanda was promptly rewarded with USD 126 million to build two roads, and billboards of Chinese construction companies are sprouting up in Kigali, the capital.

However, there are important differences regarding development progress, nowhere more so than when looking at gender equality. Rwanda has made huge advances in this area in recent years. According to the 2017 Global Gender Gap report, Rwanda is in 4th place globally, nestled between high-income Finland and Sweden. The country boasts the world’s highest female labor-market participation rate and the largest proportion of parliamentarians who are women—an impressive 61%. These striking statistics are partly a result of necessity; the 1994 genocide led to a dearth of men in society, with many killed, arrested, or forced to flee. In contrast, Ethiopia languishes in 115th place, with female labor-market participation nearly 10 percentage points lower than in Rwanda. That said, the election of Abiy Ahmed as Ethiopian prime minister earlier this year has revived hopes that women will begin to play a more prominent economic role.

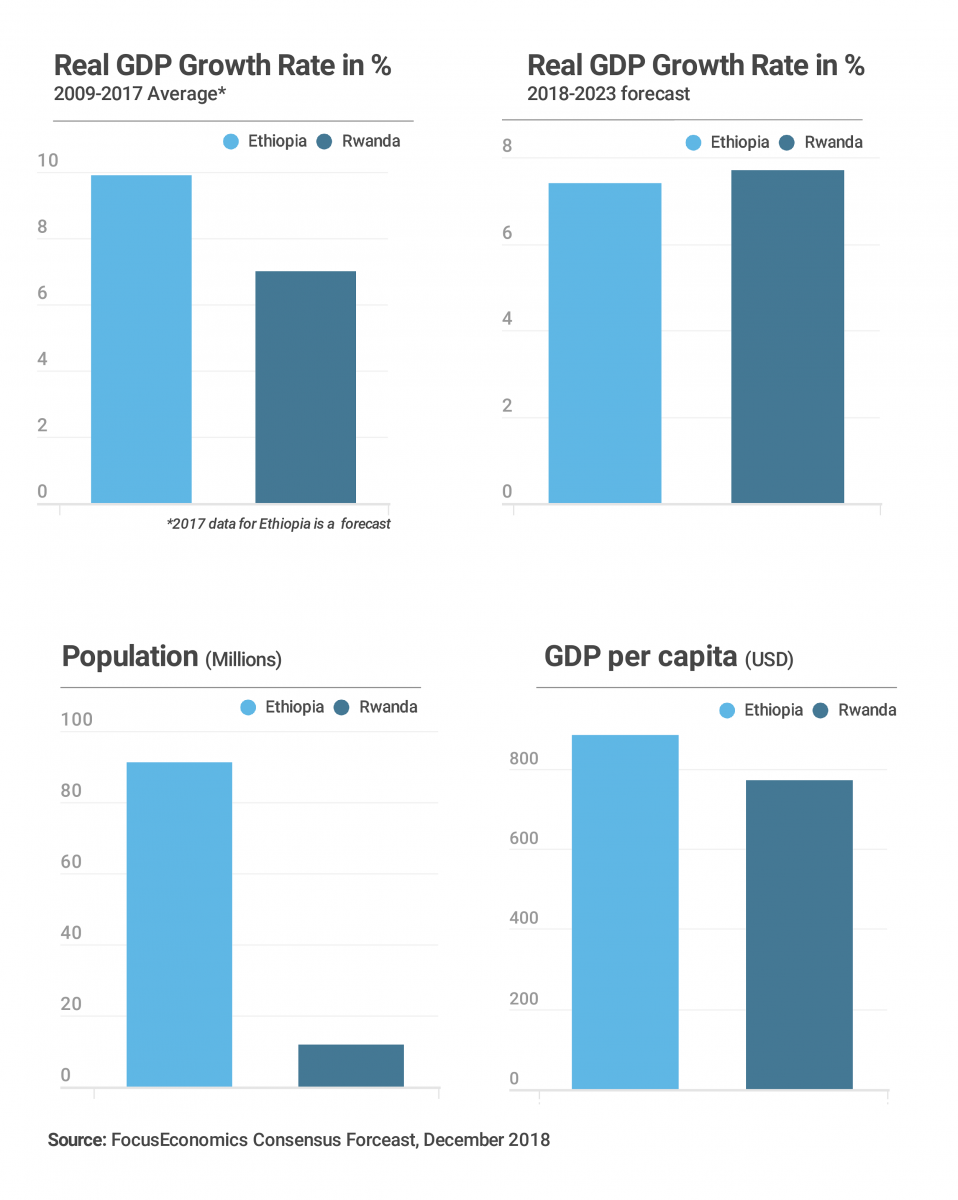

The outlook for Ethiopia and Rwanda is bright. Our panelists expect growth to average over 7% in both countries through to 2023—almost double the regional average—supported by FDI inflows, budding private-sector activity and surging exports. Current account deficits are expected to narrow, with fiscal deficits remaining at manageable levels.

Economic progress, however, won’t be completely serene. External debt—particularly bilateral debt with China—is a concern, with Ethiopia already forced to request a restructuring of its loans. Simmering civil unrest in Ethiopia could boil over, while Rwanda will be vulnerable to developments in its volatile neighbor, the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Looking further into the future, the prospect of automation in the manufacturing sector and widespread 3D-printing, which could see firms shifting production back to developed markets, could deal a blow to Ethiopia and Rwanda’s aspirations of nurturing export-oriented goods-producing sectors. Moreover, climate change could hamper agricultural production, which is still a key component of GDP in both economies.

Yet these longer-term challenges are shared by the entire continent, and competent policymaking ensure Ethiopia and Rwanda are better placed than most African nations to adapt—in the same way that foresighted leadership has been the lodestone of both economies’ metamorphosis since the 1990s.

As Rwandan President Paul Kagame said in a speech in 2014: “After 1994 everything was a priority and our people were completely broken. But we made three fundamental choices that guide us to this day. One—we chose to stay together. Two—we chose to be accountable to ourselves. Three—we chose to think big.”