Angola’s capital Luanda and Lisbon, Portugal, have been twinned since 1988, and in many respects the similarities between the two cities are evident. Both are Portuguese-speaking metropolises. Both represent the undisputed beating economic heart of their respective countries. And as seaports, both were built on the back of the maritime industry—Lisbon as an entrepôt for trade with Africa, Asia and the Americas, and Luanda as a departure point for slaves shipped to Brazil.

But in one crucial aspect, the two are poles apart: demographics. While Luanda is among the world’s fastest growing conurbations thanks to a baby boom since the end of the country’s civil war in 2002, Lisbon is broadly stagnant, while Portugal as a whole has seen its population dwindle in recent years.

This dichotomy plays out on a global scale, with what is arguably a record demographic gulf between young, booming developing nations—chiefly in Africa—and rapidly aging or declining populations in many other parts of the world.

In both cases, the economic consequences are profound. Rapid population growth implies a swelling workforce: While this presents immense economic opportunities, it also comes with risks, particularly as difficulties absorbing new entrants to the job market could endanger social stability. In contrast, population aging is set to put extra pressure on public finances, spark labor shortages and provoke profound shifts in consumption patterns. In both cases, the role of governments will be critical in allowing countries to ride out these demographic fluctuations.

Demographic divergence

A little over half a century ago, the world was a much more homogenous place. Rich and poor countries alike were young and growing swiftly. The West in particular was basking in the glow of a post-WW2 baby boom, as soldiers returned home from years of conflict, and marriage rates and living standards soared. The global population went from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 3.7 billion by 1970, with annual population growth running at around 2% in the period.

However, things began to change from the 1970s—first in Europe and North America, but later in Asia and Latin America too. In these regions, a combination of industrialization, greater access to contraception and the changing role of women in society led to nosediving fertility rates and a rapid increase in the median age of the population. While pockets of high fertility still exist in these areas, they are the exception rather than the norm, often occurring in conflict-ridden countries such as Afghanistan, Haiti, Iraq and Yemen.

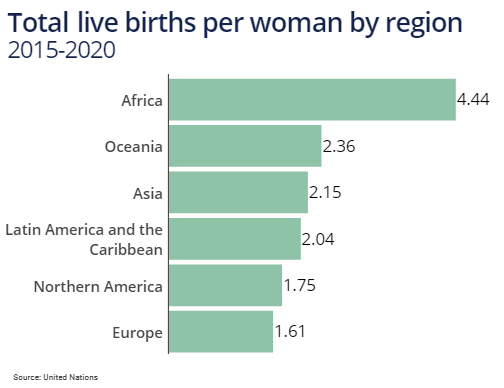

Only in Africa have fertility rates remained stubbornly high virtually across the board, and far above the replacement value of 2.1 children per woman required to stabilize the population in the long term. While this is partly due to a lack of economic development, African countries also tend to have markedly higher fertility rates than nations from other parts of the world with similar GDP per capita, suggesting powerful cultural factors are at play.

The upshot is that by the year 2100, close to 40% of all people on the planet will be African, up from a mere 17% today, according to UN projections. At the same time, Europe’s share of the global population will sink from 10% to below 6%, while Asia’s share will plummet from 60% to 43%.

Africa rising

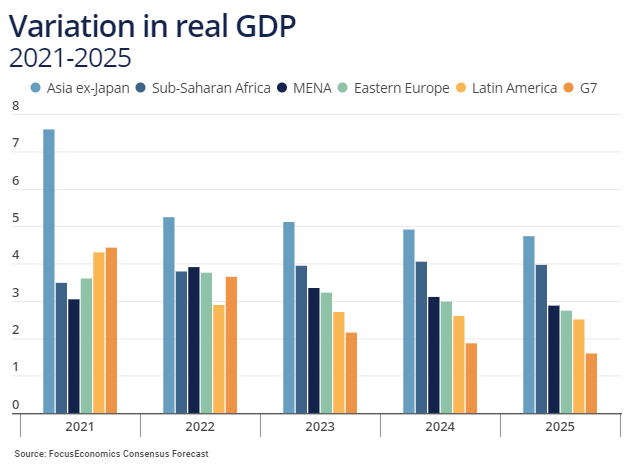

“The unfolding demographic story in Africa alone is enough to make a compelling case for a brightening future”, eulogized the Economist Intelligence Unit in 2015. Such optimism about the continent among analysts is widespread, and the rationale is clear: The booming consumer market is set to spur domestic demand, while long-term efforts to knit the continent’s disparate patchwork of national markets into a more coherent whole have recently borne fruit, with the African Continental Free Trade Area (AfCFTA) coming into force from 1 January this year. In time, this should boost firms’ competitiveness, encourage inward investment and lead to greater economies of scale. Over the next five years, our panelists see economic growth averaging close to 4% in Sub-Saharan Africa—the best performance among world regions outside Asia—spurred in no small part by population trends.

Moreover, Africa’s growing demographic and economic clout could in the longer term increase its representation in key institutions where it has historically held limited sway, such as the IMF, World Bank, WTO and UN. This could pave the way for changes in global economic governance which favor the continent—particularly in sensitive areas such as climate change mitigation and corporate tax reform.

But an alternative, less rosy vision is all too easy to imagine: Of a continent succumbing to social unrest as governments fail to provide jobs for the bulging number of young people joining the labor market, with instability fanned further by increasingly erratic crop production as global warming intensifies.

What is more, it is unclear whether African policymakers can rely on the playbook used with such success in Asian countries in recent decades, which involved the development of large manufacturing sectors to absorb excess labor. While African countries have low wage rates and competitive advantages in areas such as the processing of agricultural products and raw materials, many currently lack other important ingredients which spurred Asia’s industrial revolution, such as surplus savings, solid infrastructure or stable governance.

The widespread adoption of 3D printing and advances in robotics could also bring goods production closer to end users and negate the cost advantage of emerging markets, limiting the scope for the development of the continent’s manufacturing sector. As the International Labour Organization stated in a 2016 report: “The twenty-first century’s digital revolution has unleashed a new wave of advanced machines, further automating complex tasks and jeopardizing skilled workers in positions once considered difficult to automate. […] Opportunities may be lost and numerous industries may find themselves unprepared for the consequences. This is particularly true for developing and emerging economies.”

In this context, improving the threadbare social safety net and implementing active employment policies will be key to ease young people’s entry into the jobs market. Even more crucial will be reducing fertility through greater family planning and female empowerment. This would enable African countries to experience the “demographic dividend” currently being enjoyed by Asian nations such as India, Indonesia or the Philippines: A period when a large share of the population is of working age, leaving government coffers flush with cash and facilitating transformational public investment projects.

The silver economy

This dividend has run its course in most of the developed world as the baby boomer generation has retired. Now, wealthy nations are faced with the polar-opposite scenario of rapidly aging—and in some cases declining—populations. This will depress consumption and weigh on economic growth prospects in the coming years.

As Oliver Rakau, chief German economist at Oxford Economics, commented in reference to Germany: “Over the next decade, Germany’s potential output is expected to grow by about 1.0% a year, below the 1.3% average of the past ten years and trending down over time [due to] the drag from a shrinking domestic working age population”.

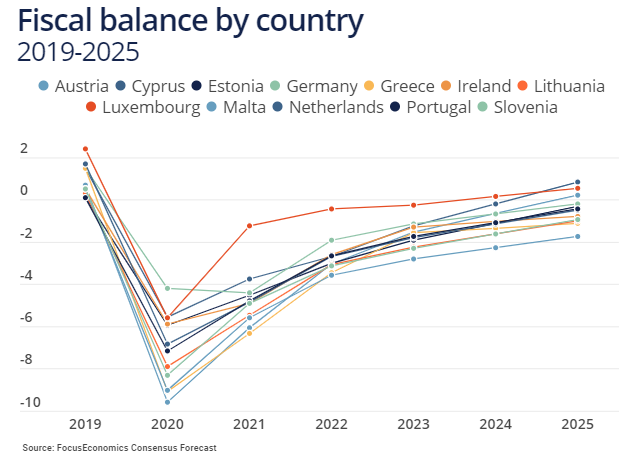

Moreover, the pressure on public budgets—which are already under strain due to the fallout from Covid-19—could be immense. According to our forecasts, of the 12 countries in the Eurozone which recorded surpluses in 2019, only three are expected to return to surplus by 2025: Getting the fiscal books back in the black further ahead will be complicated by greater age-related health and pension spending and muted tax revenues as labor force growth slows.

There are steps governments can take to mitigate these trends. Increasing participation rates—particularly of women, who tend to be underrepresented in the labor force—boosting fertility, raising retirement ages and encouraging immigration are all surefire ways of stoking growth and improving public finances.

But such reforms can prove politically sensitive. Last year the French executive backed down on proposals to raise the full-benefit retirement age to 64. In Japan—the world’s oldest nation—despite recent immigration reforms to encourage more foreign workers amid chronic labor shortages, the government is wary of the public backlash that could arise from a broader opening-up. And in Western European countries such as Germany or Italy, discontent over past open-door immigration policies has led to a surge in support for the far-right, prompting a broader hardening of political attitudes towards new arrivals.

Plus, past experience shows that depressed fertility levels prove hard to shift. In South Korea for instance, the fertility rate is the world’s lowest and has continued to decline in recent years despite myriad public policies, from family-friendly tax changes to subsidized childcare—and most recently direct cash handouts per child.

While aging nations are almost universally concerned with the potential negative economic impact, there are upsides. Scarcity of labor could support wages and encourage investment in automation and machinery for example, boosting productivity. Longer life expectancy, coupled with fewer children to care for, bodes well for savings rates, which—if channeled effectively—should increase the capital stock.

“As populations age and grow more slowly, GDP and national income growth will most certainly slow down, but the effect on individuals—as measured by per capita income and consumption—may be quite different,” wrote professors Ronald Lee and Andrew Mason in an article published by the IMF in 2017. “A graying population will mean more old-age dependency, to the extent that these people do not support themselves by relying on assets or their own labor. But it may also bring more capital per worker and rising productivity and wages, particularly if government debt does not crowd out investment in capital. Whether population aging is good or bad for the economy defies simple answers. The extent of the problem will depend on the severity of population aging and how well public policy adjusts to new demographic realities.”

For richer, for poorer

Such disquisitions will be far from the minds of the denizens of Lisbon and Luanda when debating whether to start a family. Instead, more prosaic concerns over household finances, career prospects, education costs and cultural expectations will be the order of the day. But while each individual decision to have children may be inconsequential, the accumulation of millions of such decisions will have a radical impact on the two cities and their respective economies in the coming decades—and by extension the lives of all inhabitants.

Within 15 years, Luanda is set to be among the world’s largest conurbations, with over 14 million inhabitants. In contrast, Lisbon’s population is set to largely flatline and slip down the global rankings—although the city will account for an increasingly large share of Portugal’s declining population as citizens are attracted by the greater job opportunities in the capital.

Only time will tell whether governments are successful at adapting to such population changes and shaping fertility in a way that enhances economic welfare. Politically unpalatable decisions will need to be taken—particularly in aging economies with large pension liabilities and ballooning health costs—and in many countries, societal goodwill towards the ruling class is at a historically low ebb.

“With the right set of policies, this era of intense demographic change can be turned into one of sustained development progress,” commented the World Bank in a recent report. “To accelerate progress, countries need to elevate efforts to sustain broad-based growth, invest in people, and insure the poor and vulnerable against evolving risks. But they must do so by taking into account demographic change. Where possible, they must capture demographic dividends. Elsewhere, adaptation is required. Everywhere, demographic change must be turned into opportunities for development and improved well-being.”