- FE: How has February’s military takeover impacted your forecasts? What are the main risks to your GDP outlook?

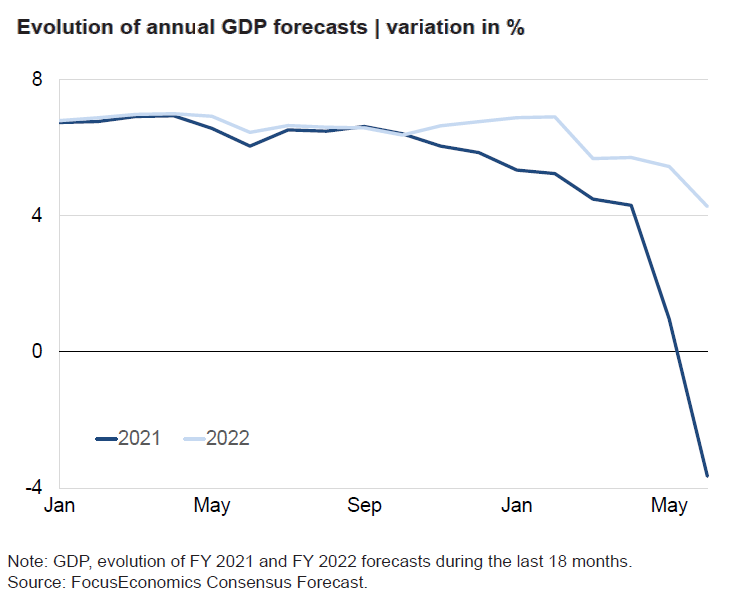

Fitch: We expect all aspects of GDP by expenditure to suffer this fiscal year FY2020/21 (October 2020–September 2021) and forecast a 20.0% contraction, with risks significantly weighted to the downside. Consumer spending will face significant pressure from income loss as a result of job losses and job absenteeism across the economy due to both weaker economic activity and the ongoing civil disobedience movement.

Mekong: Our forecasts have been revised heavily downward since 1 February. Economic activity is in decline, with the economy headed for a deep recession. Domestic marketplaces are typically still open but prices are rising and many imported goods are no longer available. This situation is not likely to change anytime soon. With ethnic armed groups slowly uniting behind a separate ‘National Unity Government’ and armed civilian ‘defence forces’ emerging in many towns and cities across the country, Myanmar is edging closer to all-out civil war. We expect the economic situation to get worse before it gets better.

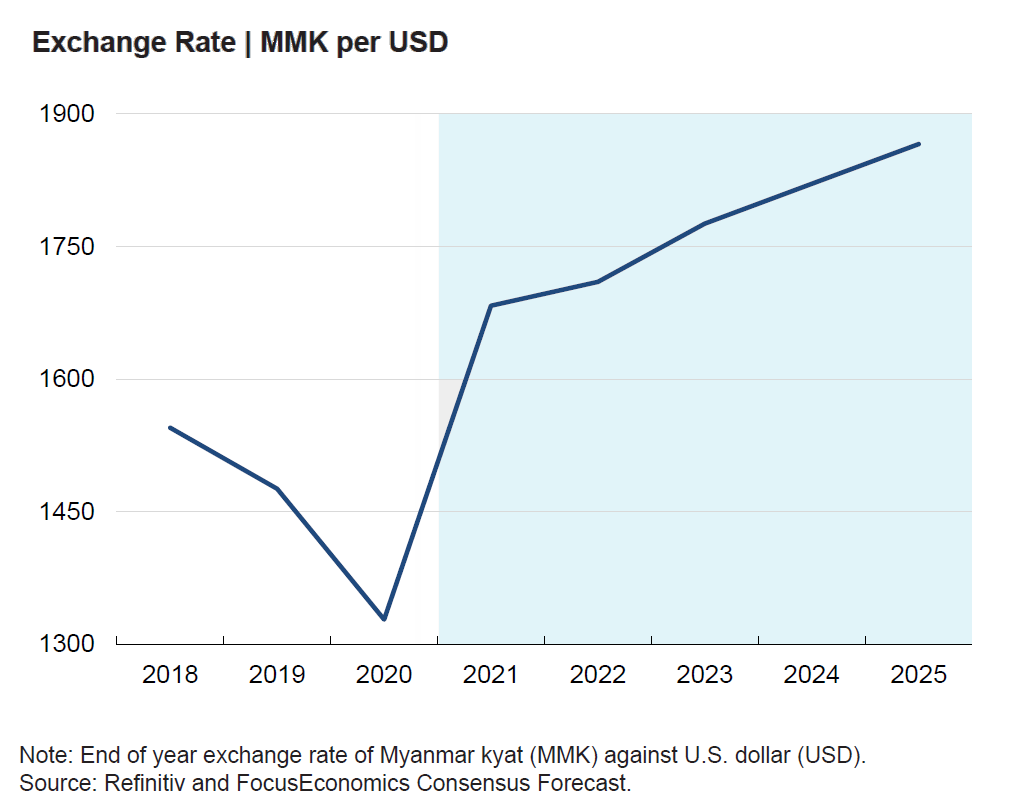

The real risk moving forward is that of an all-out banking crisis. Cash shortages are pronounced, with long queues outside bank branches and ATMs. To combat this, the Central Bank has imposed daily withdrawal limits, but people are losing faith in the system. The value of the kyat has fallen significantly against the U.S. dollar and businesses are increasingly demanding payments in cash rather than electronic transfers. Concurrently, the price of gold has increased as people seek safer alternatives [to the local currency]. Should an insolvency crisis follow, the entire economy could collapse. GDP forecasts may need to be revised down still further. The military do not have a strong track record for proficient monetary policy. The longer they remain in power, the bleaker the economic outlook.

- FE: Western countries have adopted a stricter approach compared to regional peers, with the imposition of targeted sanctions. Do you expect ASEAN countries to also resort to sanctions or maintain their current stance?

Fitch: We expect the ASEAN countries to maintain a less confrontational approach and instead continue to attempt to engage the Myanmar junta government in dialogue. We do not expect ASEAN’s intervention attempts to be effective at restoring democracy in Myanmar

Mekong: ASEAN are all about non-interference and their response has so far been weak. The summit in Jakarta in April showed signs of promise but the outcome was disappointing and appears to have made no difference to the actions of the junta. Moving forward, sanctions from ASEAN are unlikely—more dialogue and negotiations will be the way.

- FE: Do you expect China to avoid taking a hard stance on the military coup? Do you see any changes with regard to trading relations with China?

Fitch: We do not expect China to take a hard stance on Myanmar’s coup. China has consistently maintained that the coup is an internal matter for Myanmar in which it will not intervene. That said, while China is unlikely to intervene directly in Myanmar, it will continue to seek to prevent internationalisation of the Myanmar conflict. At the government level, trade relations with China are unlikely to change. However, at the private sector level, it appears that Myanmar businesses are actively avoiding purchases from Chinese suppliers due to the perception on the ground that China has been supporting the military coup.

Mekong: China has never openly condemned the coup and has been in talks with both the junta and the legitimate shadow government. It seems that on the one hand, Beijing does not want to allow Western democracies to establish a stronger foothold in the region, but the current civil unrest is hampering Chinese business interests and endangering Chinese citizens in Myanmar. Anti-Chinese sentiment has grown significantly over the past few months. Many in Myanmar see Beijing as complicit in the actions of the Tatmadaw [Burmese armed forces] and are angry that China isn’t doing more to stop the violence. Moving forward, it seems most likely that China will maintain its current stance. There is little pressure from other actors—ASEAN, UN etc.—for them to do anything drastically different. But China’s decision to not come down hard on the junta may hurt in the long term. We are already seeing boycotts of Chinese goods, which may be signs of a permanent downward shift in Sino-Myanmar trading.

- FE: What is your trade outlook for Myanmar more generally?

Fitch: We expect both exports and imports to weaken significantly. Western sanctions, logistical challenges, and the domestic turmoil, amongst other factors, will drive major global apparel brands away from sourcing from Myanmar’s factories. Food exports will also fall given growing food insecurity in the country, which will encourage hoarding domestically. We see resource exports as the only bright spot. Imports will fall due to weaker domestic demand and construction activity, as well as a much-reduced need for textile inputs for apparel manufacturing amid weakening apparel export orders.

Mekong: Western trade will likely remain depleted until the junta is gone. Regional trade will resume slowly but any large-scale businesses will likely stay away—no one wants to be seen doing business with the military. Further sanctions may exacerbate this.

- FE: What is your outlook on foreign exchange? Do you expect the military junta to maintain the managed float system?

Fitch: We expect persistent weakness for the kyat over the coming years due to fixed investment outflows from the country and increased need for essential imports such as food, all while export earnings continue to suffer under the current political turmoil. We believe that the managed float is likely to stay, although should capital outflows accelerate, we cannot rule out the reintroduction of stricter capital controls.

Mekong: The kyat will fall further still and cash shortages will continue. With exports down, foreign exchange is also in short supply and the junta will be struggling to sustain even themselves, let alone the rest of the economy. Limiting access to foreign currency is a key lever against the regime. It follows that a managed exchange system will become untenable. The CBM [Central Bank] has already been selling its stocks of USD to try and stabilize the kyat with little success. It will simply not have enough FX reserves to maintain this. Nor does it have enough reserves of domestic currency to meet the current needs of commercial banks.

- FE: What is your inflation outlook for Myanmar and what are the reasons behind it?

Fitch: We forecast average inflation of 6.2% over 2021, with a calendar year-end reading of 9.0%, up from our 3.7% estimate over 2020. Key to our high 2021 forecasts is a significantly weaker kyat, which will exacerbate already higher year-on-year global oil prices as well as make essential food imports more expensive. There are already food shortages across parts of the country, and we expect this to worsen to more areas over the course of the year as existing food supply is gradually exhausted and civil conflict worsens supply disruptions.

Mekong: We forecast a rising rate of inflation [2021: 8.4%]. Food prices are rising pretty much across the board, particularly for meat and fish. The military do not have a strong track record for monetary policy and there is a risk they will try and print their way out of this crisis. Interestingly, the junta is struggling to produce more banknotes because the ink is normally imported from a firm in Germany who ceased engagement with Myanmar in late March. This may be no bad thing for long long-run inflationary pressures and continued cash shortages may work to keep prices low.