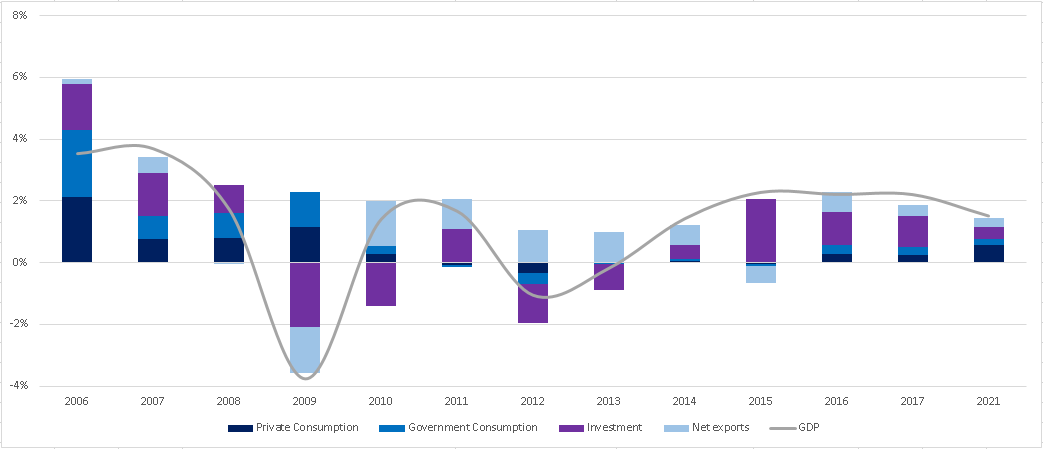

The Netherlands is one of the countries that is highly vulnerable to the economic consequences of Britain’s planned exit from the EU. As the Netherlands’ third-biggest trading partner, the UK accounts for roughly 3.3% of total employment and nearly 3% of nominal Dutch GDP through trade. Preliminary government studies posit that Brexit could shave between two and three percentage points off nominal GDP. Negative effects could extend, however, beyond that. The contribution of net exports to GDP growth in the Netherlands has grown over the years at the expense of private consumption (see figure 1). Private consumption, in addition, depends in large part on the performance of export-related sectors, so the economic fallout of Brexit is likely to extend beyond the loss of net export income.

Figure 1: Contributions to Growth

Source: Central Bureau of Statistcs (CBS)

Click on image to see larger version

Although the UK will remain a part of the EU and its single market until at least March 2019, meaning that business should continue somewhat as normal until then, some effects are already beginning to appear. Reports have emerged that British orders and investments in the Netherlands are being postponed or cancelled, while Dutch investments in the UK are also taking a hit. The prospect of Brexit has resulted in a rapid depreciation of the pound, which continues to linger at low levels; a weak pound reduces the return on investment for Dutch firms with investments in the UK. Of all Dutch foreign direct investments, 11% are directed towards the UK. At the end of 2015, Dutch firms had EUR 454 billion invested in the UK.

The weak pound is also a detriment for Dutch exports to the UK. In the first half of the year, exports of goods to the UK fell 2%, lagging behind the rest of the EU. Furthermore, the Dutch manufacturing sector has an export dependency rate of around 70%: For every euro earned, 70 cents result from export-oriented activities. The manufacturing sector is particularly interwoven with the British economy and more vulnerable to exchange rate volatility; it also has greater export dependency than other sectors (the export dependency rate of the Dutch economy as a whole is 32%). While policymakers in Westminster speak of creating a special relationship with the EU, historical precedence dictates that in terms of trade deals with the EU, there are roughly three options.

One option would be a hard Brexit, in which the UK walks away without a deal and trade resumes under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. In this scenario, the UK would likely apply the EU’s current WTO schedule of tariffs for Most Favored Nations, through a process known as rectification. Going beyond rectification, modifying the tariffs and quotas would require lengthy negotiations . The current WTO schedule assumes that the 28 members operate as a coherent economic bloc. Keeping the common external tariff of the EU while breaking free from Brussels would leave supply chains very susceptible to disruption: Every time goods or parts would move to and from the UK, they would be hit with a levy.

Goods are particularly prone to import tariffs, and roughly 60% of Dutch exports to the UK consist of goods. The simple average WTO tariff the EU uses for countries with which it does not have a trade agreement currently stands at 5.2%, although levies vary per product group . Dairy products are taxed 37.4 %, while wood and paper products are only subject to a 0.9% import tariff. In terms of net earnings, Dutch-made goods and services are more important than so-called “re-exports”, accounting for 2% of nominal GDP. However, re-exports, which begin as imports before being exported to the UK, are significant in terms of export value: Nearly half of Dutch export value is derived from re-exports. Moreover, the multiplier effect is reversely applicable in the scenario of a hard Brexit without a trade deal. As trade with the UK decreases, the income of people associated with it would also fall, leading to a decrease in private consumption. There would also be less demand from exporters for products and services further down the supply chain.

A second option would be for the UK to become a European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member and retain access to the European Economic Area (EEA), akin to Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein. When the UK exits the EU, and by default the single market, EFTA membership would be a prerequisite for re-accessing the single market. While most trade would continue on the tariff-free path per Article 10 of the EEA Agreement, some sectors would be excluded. Specifically, sectors such as agriculture and fisheries will be subject to levies and quotas since the EFTA does not include freedom of movement of these goods. One in ten Dutch agriculture exports are destined for the UK across the North Sea. Though a “Norway”-style agreement would soften the blow of a fall back to WTO rules, it would not be without its own pains.

The third option would be to follow the example of Switzerland: joining EFTA without joining EEA and signing multiple bilateral agreements with the EU. Switzerland signed seven sectoral agreements, which is not allowed under WTO rules, with the EU in 1999 called Bilateral Agreements I. Those agreements were followed by a second installment in 2010. Although they include freedom of movement of agricultural goods, they also include provisions for freedom of movement of people, provided they meet certain criteria. A Swiss-style EFTA deal would enable both sides to concede a bit from their firm positions.

Despite all the downside risks presented by Brexit, there could also be some benefits for the Netherlands. As the UK is adamant to take itself out of the EU, many banks wishing to continue operating in the European market will have to relocate. In early August, news broke that the Royal Bank of Scotland will move to Amsterdam to continue its post-Brexit European operations. In addition, a major Japanese bank, Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group , announced in mid-September that it plans to move to the Dutch capital following the Brexit. Two U.S. trading companies based in London, Tradeweb and MarketAxess , have also decided to move to Amsterdam after Brexit. Although luring banks and companies to the Netherlands could bring some employment opportunities, in all likelihood it would not be enough to offset the losses suffered from a hard Brexit.