Click on the image to open a full-size version

The ruling Popular Party (PP) is quick to claim credit for this revival. Soon after taking office in 2011, it introduced sweeping labor market reforms making it easier to lay off workers, reducing dismissal costs and shaking up collective bargaining laws.

“The reforms […] were important for changing the business climate, thus nurturing a job-rich recovery,” argues Raymond Torres, Director of Macroeconomic Analysis and Forecasting at Funcas.

They also had a tangible impact on firms’ bottom lines, according to Angel Talavera, Senior Eurozone Economist at Oxford Economics. “The main accomplishment of the reform was to make wages more flexible, which was a much-needed change for the Spanish economy, which has traditionally suffered from excessive indexing leading to unsustainable real wage growth compared to its low productivity.”

Greater flexibility has boosted cost competitiveness, which evaporated during the boom years. According to OECD figures, unit labor costs—the average cost of labor per unit of output—in Spain have fallen by an average of 0.8% annually since 2010, encouraging firms to ramp up hiring and leading to rapid growth in export-oriented sectors.

A nuanced picture

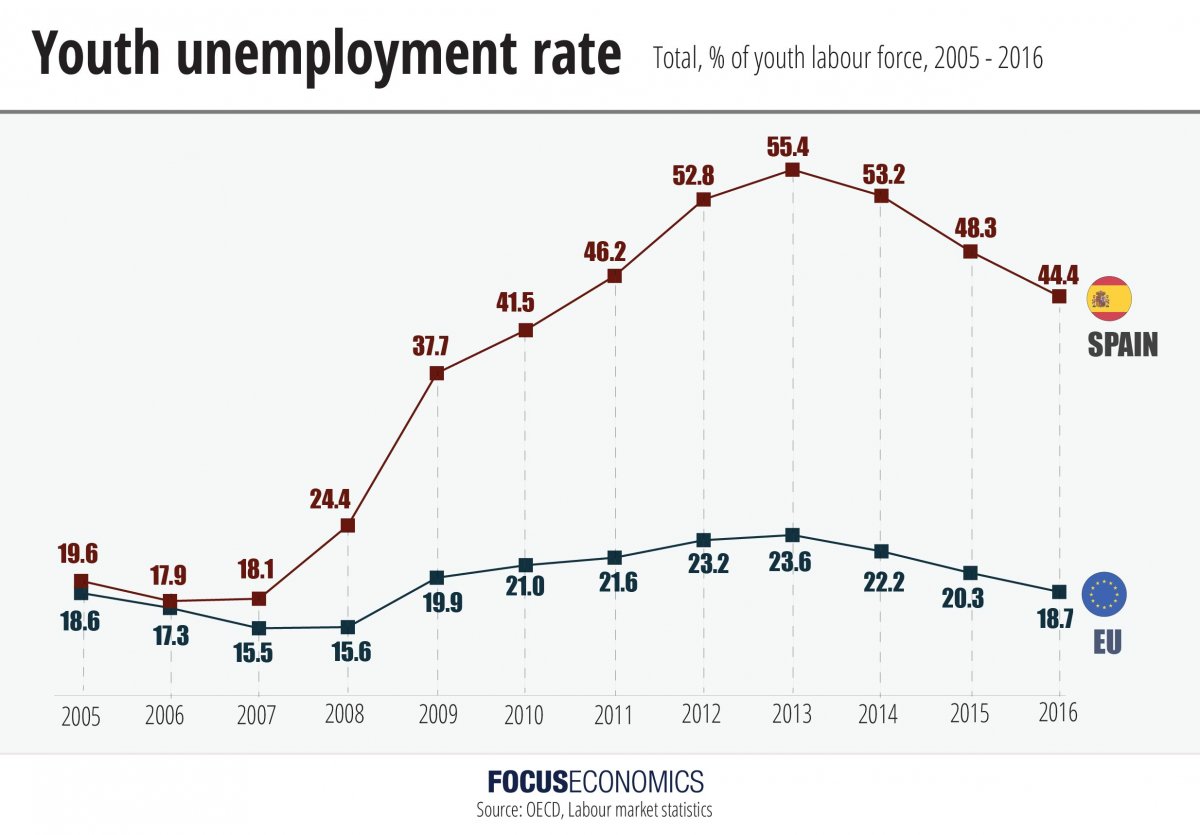

However, despite the rate at which new jobs are appearing, the labor market still suffers from significant flaws.

“The [Popular Party’s] reform did nothing to solve the issue of duality, that is the high prevalence of temporary workers”, argues Angel Talavera. Roughly a quarter of all jobs in Spain are temporary, far above the EU average. They are often poorly paid, of short duration and provide little incentive for firms to invest in employees’ professional development.

Young people are particularly likely to hold such short-term posts, and Laura Avizanda is no exception. “[My contract] is temporary, it’s for three or four months,” she comments. Virtually all her friends are in a similar boat; she cites the case of a friend who is “coming to the end of her second 6-month contract.”

Far from rising in sync with the economic recovery, the number of workers aged 20–24 who hold permanent contracts has fallen in recent years, while the number on temporary contracts has shot up. According to a recent IMF report, the number of Spanish workers who sign more than ten contracts a year soared from 150,000 in 2012 to 270,000 in 2016.

This alarming evolution has likely played a role in depressing young people’s wages; recent data from the Statistical Institute (INE) shows that young workers were still earning notably less in 2016 than they were five years earlier.

The way the labor market is designed discourages permanent hires. Severance pay in the case of fair dismissal is a mere 12 days for those in temporary posts, but 20 days per year worked for those on a permanent contract. For many firms, this difference in dismissal costs between temporary and permanent contracts represents an insurmountable barrier, and as a result transition rates from temporary to permanent contracts are far below the EU average. Angel Talavera speaks of “an environment where many firms find it preferable to hire and fire at will than invest long term or adjust through alternative measures.”

Despite their precarious nature, recent university graduate Laura Avizanda considers that short-term contracts serve a purpose when used as a “trial period.” Raymond Torres concurs: “A temporary contract can be useful for acquiring work experience and making a first step in the labour market.”

But he adds, “However, they [temporary contracts] can become dead-ends, with young cycling from one temporary job to the other, with unemployment spells in between.” The key, he believes, is to make them “stepping stones” to full-time positions.

Alongside pervasive duality, the education system is another key element hampering young people’s labor market outcomes. At first glance this may seem strange; Spanish students score close to the OECD average on PISA tests for mathematics, science and reading. At 40% the tertiary education attainment rate is higher than in most other EU countries.

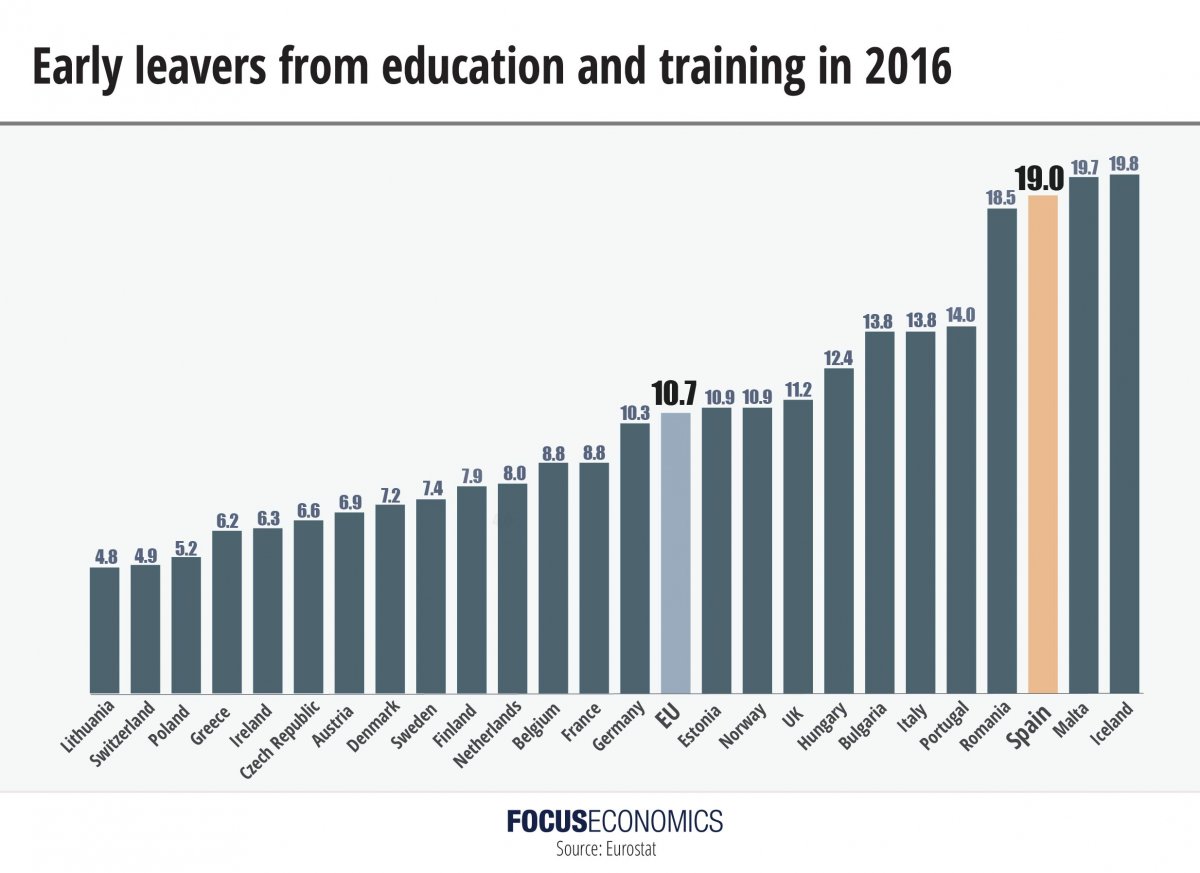

However, many young people fall by the wayside long before reaching university. The percentage of early school leavers—those who have at most only completed lower secondary education—is higher than in any other European country bar Malta.

The problem is particularly acute among young males. Before the crisis, many were lured from school by the prospect of making easy money in the construction industry. Although the percentage of early school leavers has dipped somewhat in recent years, there is a clear danger that, as the economy recovers, young workers are once again attracted by the same siren call, particularly in regions that are dependent on low-skilled industries.

Click on the image to open a full-size version

Those who do make it through the education system often find themselves spat out into the labor market with a degree and skillset that employers simply do not need. According to a recent European Commission report: “At 37% Spain also has the highest proportion in the EU of graduates working in occupations not requiring university education.” Graduates in the social sciences and humanities have particularly poor labor market outcomes, the Commission says.

This problem is exacerbated by students’ lack of awareness of career options before embarking on higher education courses. And there are a lack of alternatives to university; the number of young Spaniards in vocational training programs is far lower than in most neighboring countries.

The significant skill mismatch is also reflective of weak linkages between employers and universities. “Unlike in the most successful countries, there are relatively few opportunities to combine education with work experience,” argues Raymond Torres.

Laura Avizanda has first-hand experience of this, and admits to having felt “slightly lost” when she started her job due to not having undertaken a work placement while at university.

The unclear path ahead

Whether it’s tackling temporary contracts, getting early school leavers into work, or making graduates more attractive to employers, other countries have shown that public policies can make a huge difference. As Raymond Torres says: “In all these areas, good practices exist.”

Temporary and permanent contracts could be melded into a single open-ended contract with gradually increasing severance pay. There is also the Austrian “backpack” model, which allows workers to carry entitlement to severance pay from job to job, regardless of their current contract type.

Denmark and Germany are proof of how setting up one-stop shops offering unemployment benefits and services such as individualized counselling, tailored job offers and job search training can dramatically improve the functioning of labor markets. And Germany leads the way in providing high-quality vocational education, combining academic studies with ample hands-on experience.

However, whether the Spanish government is currently able or willing to carry out such changes is another matter. Political momentum has ebbed in recent years, following a large reform package in 2012 and follow-up measures in 2014 and 2015. This is partly because the strong economic recovery has made further modifications less pressing.

But it also reflects a fractured parliament. The PP lost its lower-house absolute majority following elections in December 2015, and several of the main opposition parties have campaigned to strike down the government’s reforms. Although an agreement with the liberal Citizens party could probably be reached, support from other groups would be necessary to get any bill through the chamber. In the currently contentious political atmosphere, that is a tall order.

Recent months have seen some movement, however. The government is currently in talks with trade unions and employers over a reform that would gradually match the severance pay of temporary and permanent contracts over a period of 3 years. But with temporary contracts lasting on average a mere 50 days, the impact may be limited.

A “National Educational Pact” among all the major political parties, currently being discussed in a congressional committee, could prove more groundbreaking. The initiative aims to separate the debate over education reform from partisan politics and tackle longstanding deficiencies. Getting such a kaleidoscope of political ideologies on the same page will be a daunting task, but the reward could be great.

The cost of not implementing any reforms could be even greater. The longer young people remain unemployed, the greater the risk that they become permanently disenfranchised. And with the challenges posed by globalization and digitalization, ensuring Spain’s education system matches the demands of the labor market is paramount if the country is to avoid leaving many young people behind economically.

However, government reforms in the pipeline and the changing job environment are far from being at the forefront of young people’s minds. All too aware of the harrowing experiences faced by so many others in recent years, many of the current cohort are simply thankful to be working, despite the uphill battle they face to secure stable, well-paid employment. “Things could be worse,” says Laura. “I would rather it was a permanent contract, to be honest. But it’s a start, and a good way to get experience. I’m just glad to have found a job.”

Photo by rawpixel.com on Unsplash

Sample Report

5-year economic forecasts on 30+ economic indicators for 127 countries & 33 commodities.