What is forecasting?

Let’s back up a bit first. What is forecasting and why is it used? Well, forecasting is basically a fancy way of saying, predicting the future. A dictionary definition of forecasting is the act of making predictions or estimations of the future or a future trend.

Whichever way you want to say it, predicting the future sounds a lot like it should involve tarot cards, crystal balls, and psychics, however, forecasting is actually a very real, complex and sophisticated process.

Economic forecasting, more specifically, is a type of forecasting that is used more to predict the future condition of economies or certain sectors of the economy. This is done by analyzing historical and current data, utilizing sophisticated statistical models to project future performance of the economy or sectors of the economy.

Why is forecasting used in business?

Forecasting is used by organizations of all types to reduce the inherent uncertainty of the future in an attempt to make informed decisions on vital business processes such as budget allocation.

Why is economic forecasting so difficult?

When we think of forecasts, usually the first thing that comes to mind is the weather forecast. What often comes to mind next is that those weather forecasts so often turn out to be wrong. However, we shouldn’t knock the weatherman because predicting the future of anything is a daunting task, to say the least.

Now, let’s think about predicting the future behavior of something as complex and enormous as an entire economy. Now that is truly a tough job and it makes accurate forecasts difficult to come by.

There are a few reasons for the complexity of economic forecasting. The first is that economies are in perpetual motion and therefore extrapolating behaviors and relationships from past economic cycles into the next one is tremendously complicated. However, the biggest problem has to do with the massive amount of raw economic data available.

In an ideal world, economic forecasts would consider all of the information available. In the real world, however, that’s pretty close to impossible, as information is scattered in myriad news articles, press releases, government communications, plus the aforementioned mountain of raw data.

Although it might sound like having all of that information would be advantageous, nothing could be further from the truth. There are thousands of economic indicators and data available and these tend to produce a vast amount of statistical noise, making the establishment of meaningful relations of causation between variables a serious challenge.

The question then is, how can we cancel out all of that noise to get a more accurate forecast? This is where the wisdom of the crowds comes in and for FocusEconomics, the Consensus Forecast.

The wisdom of the crowds

Sir Francis Galton, a Victorian polymath, was the first to note the wisdom of the crowds. At a livestock fair he visited in 1906, attendees were given the opportunity to guess the weight of an ox. The closest to the actual weight would win the prize, which happened to be the meat of the entire slaughtered ox.

Although this might not sound like a great prize to many of us today, to those attending the fair 110 years ago, it must have sounded pretty good because there were over 750 participants to try their hand at guessing the ox’s weight. After all of the guesses were talied, the interesting thing to note was that nobody got the exact weight of the cow right, but everyone got it right. Doesn’t make sense? It will all become clearer shortly.

No one got the weight of the cow spot on, but Galton took all of the guesses from each participant and calculated the mean average. Incredibly, the average turned out to be the exact weight of the ox: 1,198 pounds.

You might be thinking it was a one-off, however, this was no fluke, there is actually a science to this. The wisdom of the crowds is currently used in many different areas, from economic forecasting to politics to psychology. The basic idea of the wisdom of the crowds is that the average of the answers of a group of individuals is often more accurate than the answer of any one individual expert.

You might be asking yourself, “how could that be?” Well, think back to that noise we mentioned earlier that makes economic forecasting so complicated. The theory with the wisdom of the crowds is that idiosyncratic noise is associated with any one individual answer, therefore, by taking the average of multiple answers, the noise tends to cancel itself out. This presents a far more accurate picture of the situation and in economic forecasting, a far more accurate forecast.

The FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast

For the wisdom of the crowds to be more accurate, it depends on the number of participants and the diversity of the expertise of each individual participant. The more participants involved and the more diverse the participants are, the lower the margin of error or in other words, the closer the average will be to the actual answer.

This is where FocusEconomics comes into the picture: we work with hundreds of economic research teams around the world. These economic research teams include investment banks, consultancies, economic think tanks and independent professional forecasting firms. Some of them work on a global scale and others are local forecasters who are on the ground in the countries we cover.

The consensus forecast borrows the idea of the wisdom of the crowds. We collect, process and analyze the information from our global network of over 900 trusted economic experts and ultimately condense that information to provide one answer, the FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast.

Quotes from academic research on the Consensus Forecast

“Consider what we have learned about the combination of forecasts over the past twenty years. (…) The results have been virtually unanimous: combining multiple forecasts leads to increased forecast accuracy. This has been the result whether the forecasts are judgmental or statistical, econometric or extrapolation. Furthermore, in many cases, one can make dramatic performance improvements by simply averaging the forecasts.”

Clemen Robert T. (1989) “Combining forecasts: A review and annotated bibliography” International Journal of Forecasting 5: 559-560

“A key reason for using forecast combinations […] is that individual forecasts may be differently affected by non-stationaries such as structural breaks caused by institutional change, technological developments or large macroeconomic shocks. […] Since it is typically difficult to detect structural breaks in ‘real terms’, it is plausible that on average, across periods with varying degrees of stability, combinations of forecasts from models with different degrees of adaptability may outperform forecasts from individual models.“

Aiolfi M. and Timmermann A. (2004) “Structural Breaks and the Performance of Forecast Combinations”: 2

Relying on a single-source forecast is risky business

As corroborated by the studies cited above, research shows that the Consensus Forecast is far more accurate than any one individual forecast the vast majority of the time.

With that said, the forecasters that partner with us are experts at what they do and therefore it is possible for an individual forecast to beat the Consensus, however, it is unlikely that they will do so consistently year after year. Even those individual forecasts that do happen to beat the Consensus one year are impossible to pick out ahead of time since they vary significantly from year to year.

A practical example from the FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast

So, let’s take a look at a real-life example to demonstrate exactly how the Consensus Forecast works.

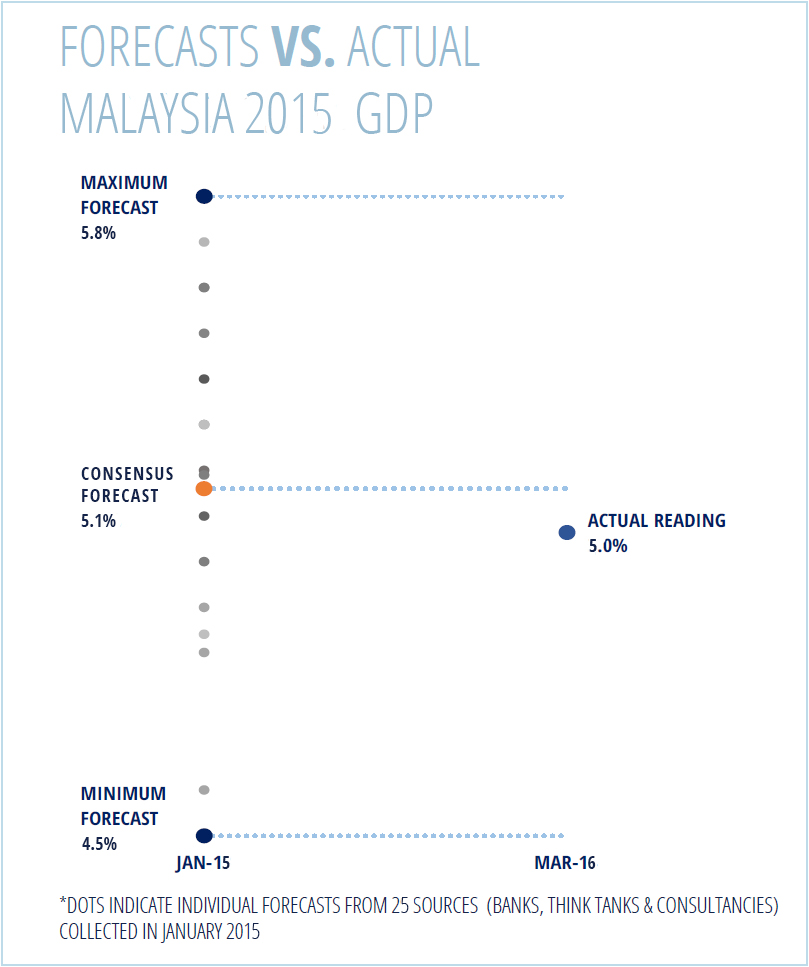

In the graph above, the Consensus Forecast for Malaysia’s 2015 GDP taken in January 2015 was 5.1%, which is marked in orange. All the other points, marked in gray, along the same axis represent the individual forecasts from 25 prominent sources taken at the same time.

In March 2016, the 2015 full year reading for Malaysia GDP came out at 5.0%. The Consensus was pretty close, right?

A few forecasts were closer to the end result, however, as mentioned previously, some individual forecasts are going to beat the Consensus from time to time, but it won’t happen consistently and it would be impossible to know which forecasts those will be until after the fact.

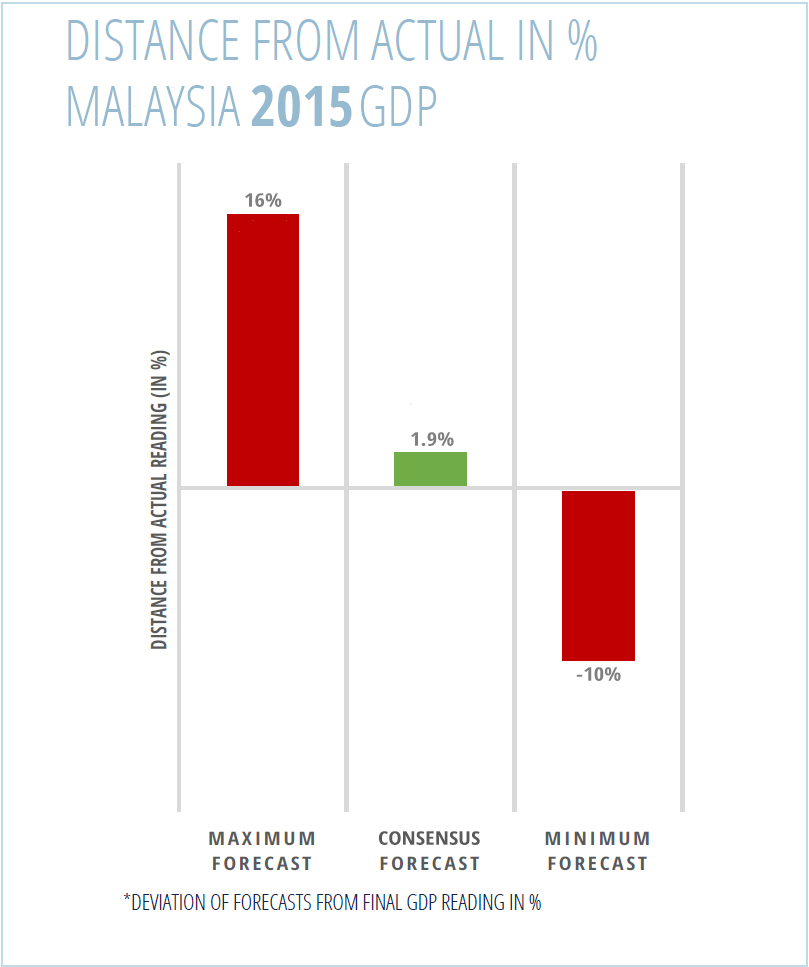

The second image uses the same example as before; 25 different economic analysts forecasted Malaysia’s 2015 GDP in January of 2015. By March 2016, the maximum forecast turned out to be 16% above the actual reading with the minimum 10% below the actual reading.

The Consensus was only 1.9% above the actual reading. By taking the average of all forecasts, the upside and downside errors of the different forecasts mostly canceled each other out. As a result, the average (consensus) forecast was much closer to the actual reading than the majority of the individual forecasts.

Reducing the margin of error reduces risk

Not only is it impossible to know which forecast will be the most accurate more than a year before the actual reading is released, but as is evident in the images above, the forecasts from individual analysts can vary significantly from one to another. The large range of individual forecasts makes choosing just one a much riskier proposition.

Admittedly, the Consensus wasn’t spot on, but it was pretty close and certainly decreased the margin of error. It is important to note that there is almost always going to be some error. But reducing that error yields a far more accurate forecast.

Most importantly, it reduces the risk inherent with economic forecasting and this is what makes the FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast so valuable. Predicting the future is not an easy business to be in.

So, with all of that said, would you like to roll the dice and pick out one or two forecasters to go with or would you rather go with the FocusEconomics Consensus Forecast for the most reliable, accurate forecasts the majority of the time? The choice is yours.