The Roots of Tulip Mania

So, what is the story with the tulip mania? Well, as some may be aware, the tulip is a national symbol of the Netherlands. The country is affectionately known by some as “the flower shop of the world.” If you’ve ever been to the Netherlands, you’ve probably seen some or visited some of the beautifully cultivated fields of colorful tulips lining the landscape of the Dutch countryside. There are countless tulip museums and tulip festivals are still celebrated annually throughout the country. The Dutch people even took their love of tulips abroad when emigrating from their homeland, starting up tulip festivals in places like New York (which Holland.com points out was originally known as New Amsterdam) and in the town aptly named Holland located in the U.S. state of Michigan.

Despite this near obsession with tulips, the flower is not native to the Netherlands. They are actually native to the Pamir and Tan Shan mountain ranges located in Central Asia primarily in modern-day Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan. They were brought to the Netherlands in the late-16th century from the Ottoman Empire where the flower had been cultivated for decades prior.

A botanist by the name of Carolus Clusius who in the 1590s had begun an important botanical garden at the University of Leiden, was one of the first to really pioneer the cultivation of tulips in the Netherlands. He had his own private garden in which he planted numerous bright and beautiful tulips and devoted much of his later life to studying the tulip and the mysterious phenomenon known as tulip breaking.

|

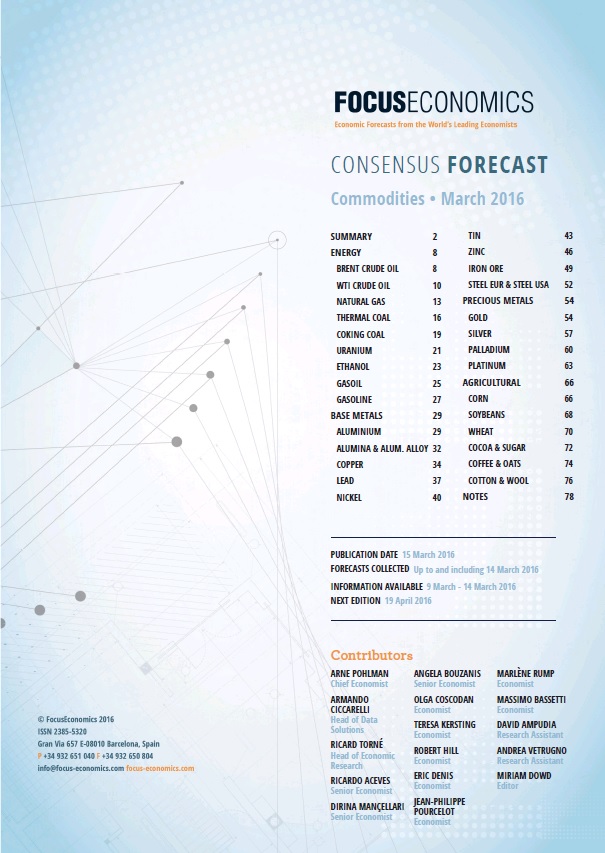

FREE Sample – Commodities Price Forecast Report Download a sample of our new Consensus Forecast Commodities report 33 commodities in the energy, metals & agricultural sectors Price forecasts, historical data, & written analysis |

Tulip breaking is key to the story of the tulip mania. It was a strange occurrence in which the petal colors of the flower suddenly changed into multicolored patterns. Many years later it turned out that these strange looking tulips were actually the result of a virus that had infected them. Nonetheless, these essentially diseased multicolored tulips did nothing but serve to ramp up the tulip craze further.

The mesmerizing diseased tulips became even more valuable than the uninfected ones and Dutch botanists began to compete with each other to cultivate new hybrid and more beautiful varieties of tulips. These became known as “cultivars” and would be traded among a small group of botanists and other flower aficionados. As time passed, the trade grew out from the group and botanists began to receive requests from people they did not know for not only the flowers, but the bulbs and seeds in exchange for money. Tulip brokerages began to open up and what was originally a “gentlemanly pursuit” turned into an all-out war for profits.

Part of what helped this interest in Tulips grow, along with people’s willingness to exchange money for them, was the fact that the Netherlands in the early part of the 1600s had become the richest country in Europe mostly through trade. During this Dutch Golden Age, not only were there aristocrats with money, but middle-class merchants, artisans and tradesmen also found themselves with extra coin burning a hole in their pockets. Basically, this meant more people were able to spend money on luxuries such as cultivars that perhaps in other European countries would not have been commonplace.

Besides the fact that people had money up and down the social class structure, the Netherlands and specifically Amsterdam already had robust trading platforms. The Amsterdam Stock Exchange opened in 1602 and the Baltic Grain Trade, an informal futures market itself, had begun decades earlier. The Netherlands was therefore primed for a new trade, which was to become Tulip Mania.

The Bubble

Tulips became the talk of the fledgling Dutch Republic. “Neighbors seemed to talk to neighbors; colleagues with colleagues; shopkeepers, booksellers, bakers, and doctors with their clients gives one the sense of a community gripped, for a time, by this new fascination and enthralled by a sudden vision of its profitability,” wrote Anne Goldgar in Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age.

By the 1620s, prices were already rising to incredible levels. One story in particular was of an entire townhouse offered in exchange for just 10 bulbs of the very special cultivar, Semper Augustus (shown to the right), that had petals that looked a bit like a candy cane. Although the offer of an entire house for just 10 bulbs was incredible in its own right, the fact that the offer was rejected outlines just how much these flowers were considered to be worth at the time.

In the years that followed it became more and more apparent that the tulip bulbs themselves were going for more money than the actual bloomed flowers. Speculators piled into the markets like wildfire, trading the bulbs rather than the flowers, which resulted in what you might call a futures market. By 1633, rather than bother with guilders, the Dutch even began using the bulbs as a currency themselves. There are numerous records of land properties being sold for bulbs.

As word spread that one could make ridiculous sums of money simply by buying and selling the bulbs, prices skyrocketed even higher. According to the BBC, in 1633 a single bulb of Semper Augustus was worth 5,500 guilders. 4 years later in 1637, the sum had nearly doubled to 10,000 guilders.

You may be wondering what a guilder is—the guilder was the Dutch currency up until the adoption of the Euro. Having said that, to put the above numbers into perspective, according to Mike Dash who wrote Tulipomania: The Story of the World’s Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused, “It was enough to feed, clothe and house a whole Dutch family for half a lifetime, or sufficient to purchase one of the grandest homes on the most fashionable canal in Amsterdam for cash, complete with a coach house and an 80-ft (25-m) garden – and this at a time when homes in that city were as expensive as property anywhere in the world.”

That was only to be the crescendo, however, as the climax of tulip mania took place in Alkmaar at an auction shortly thereafter where cultivars Viceroy and Admirael van Enchuysen sold for 4,230 florins and 5,200 florins, respectively. By the height of the tulip and bulb craze in 1637, everyone had gotten involved in the trade, rich and poor, aristocrats and plebes, even children had joined the party. Much of the trading was being done in bar rooms where alcohol was obviously involved. According to some reports, bulbs could change hands upwards of 10 times in one day. Prices skyrocketed at one point in 1637, increasing 1,100% in a month. In just over a month from 31 December 1636 to 3 February 1637, Switsers, a particularly popular bulb saw its price rise from 125 florins to 1500 florins.

The Burst

At this point, it might be pretty obvious what was to come next for the bubble. As the story is often told, almost overnight the bulb trade disappeared because as the price rose to dizzying heights, finally someone just decided not to pay, everyone lost confidence and prices plummeted. Although this is very dramatic and perhaps makes the story sound better, it may not be entirely true.

As is often the case with economic bubbles, as the price rose to a point where it was obviously so incredibly inflated, some prudent people decided to get out and capitalize on the absurd prices. Then a domino effect took place where more and more tried to sell at ever decreasing prices. The truth is that no one is completely sure what lead to the cataclysmic demise of the bulb trade, but what is certain was that it caused unmitigated pandemonium and widespread panic throughout the republic.

This is when parties involved began to stop honoring contracts. Needless to say, this was cause for much hubbub, as people realized they had bet their whole life savings or family homes on these tulip bulbs. The Dutch government even had to intervene to try to curb the fall, offering to honor contracts at 10% of the face value, however, this only worsened proceedings, as the price began to fall even farther until the bottom completely fell out.

Of course, this resulted in financial ruin for many, as the bulbs that they had paid so highly for were worth virtually nothing. Debt disputes went on for years and even those that were lucky enough to get out early were hurt later by the depression in the aftermath of the crash. The Dutch government passed the buck by making a feeble proclamation that the debts were to be settled by local city magistrates. Eventually the majority of the contracts were cancelled.

The Remembrance

Why is Tulip mania remembered? Well, beside the fact that it is a tragically hilarious story of irrational behavior by a whole nation of people, it was one of the first and most devastating bubbles of all time. For the Dutch people, it left a lasting legacy, with it’s roots running deep into Dutch society serving as a fable or a morality tale regarding inequality, teaching not to seek “inconsistent wealth before honor.” Other than that, it certainly left the Dutch wary of speculative investments for some time.

As Investopedia wrote, “The effects of the tulip craze left the Dutch very hesitant about speculative investments for quite some time. Investors now can know that it is better to stop and smell the flowers than to stake your future upon one.”

When we are school children, usually we are told during our grade school history lessons that the reason we keep records of the past is so that we can learn from the past and not do what didn’t work the first time around. The most important reason to remember the tulip and bulb market bubble, therefore, is so that we don’t let it happen again. Yet, these types of bubbles continually happen. We don’t seem to learn our lesson. As Edmund Burke said, “Those who don’t know history are doomed to repeat it.”

Author: Brian Dowd

Header image courtesy of GoToVan

Semper Augustus image courtesy of Alwyn Ladell

Originally published in August of 2016. Updated on 15 September 2017.