- At the end of May, President Biden and Republican Speaker of the House Kevin McCarthy reached a deal to raise the debt ceiling.

- Congressional approval—which is not guaranteed—would avert a damaging default.

- The deal caps government spending for the next two years, which will weigh slightly on domestic demand.

What happened:

On 27 May, President Biden and Kevin McCarty finalized a tentative agreement to suspend the government’s USD 31.4 trillion debt ceiling until January 1, 2025. In exchange, non-defense discretionary spending in the 2024 fiscal year (October 2023 to September 2024) will be roughly flat, and rise by only 1% in FY 2025. The deal will also speed up the approval process of energy projects and impose tougher work requirements on some recipients of government aid.

Next steps:

The House of Representatives will vote on the deal on Wednesday, 31 May, with Senate votes to follow in subsequent days. Given that the Republicans hold a majority in the House and the Democrats in the Senate, the agreement will require bipartisan support in order to pass. If Congress does not pass the deal, the government could run out of money to pay its bills in June, leading to default, sharp government spending cuts and financial turmoil. Given the severe consequences of the failure to suspend the debt ceiling, the deal is likely to be approved. However, there is still a non-negligible risk of it being scuppered by right-wing Republican or left-wing Democrat members of Congress.

The economic impact of the deal:

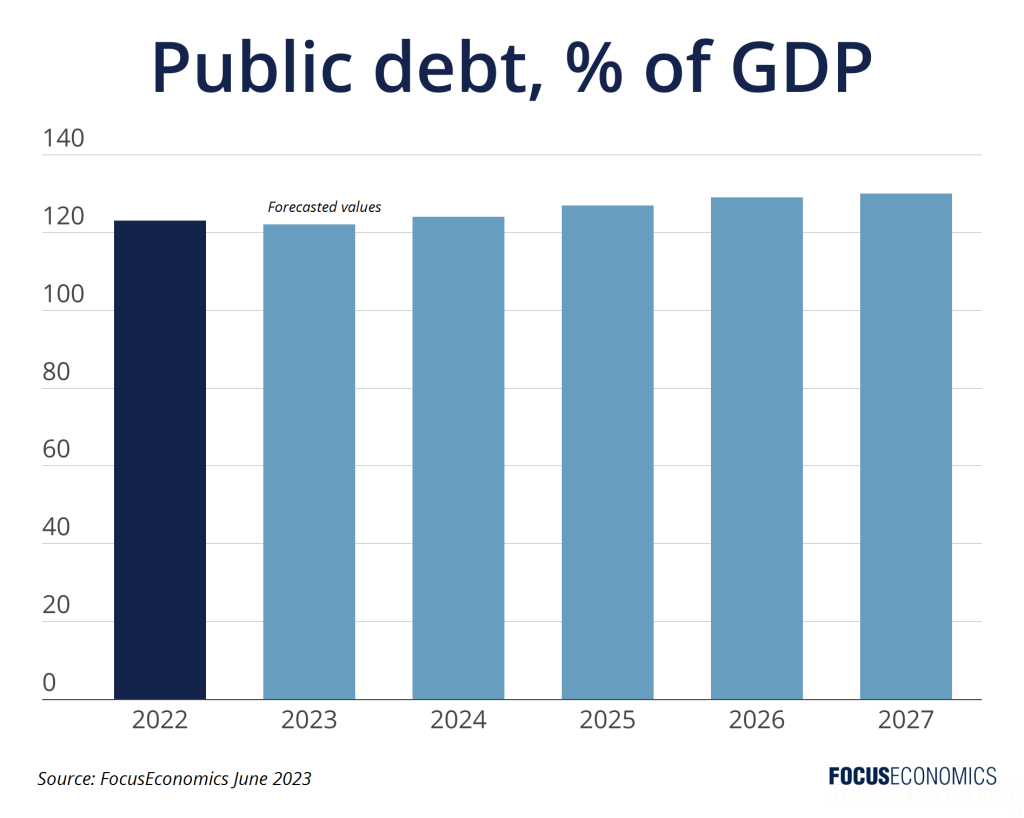

Limits to government spending will weigh on domestic demand over the next few years. However, the impact should be mild: Discretionary federal spending is only around a quarter of total federal spending, and the high degree of decentralization in the U.S. means that a large share of government expenditure is under the remit of state and local governments.

On the economic upshot, Goldman Sachs analysts said:

“The spending deal looks likely to reduce spending by 0.1-0.2% of GDP yoy in 2024 and 2025, compared with a baseline in which funding grows with inflation. That said, the boost to funding Congress approved late last year for FY23 was so large (nearly 10% yoy) that overall discretionary spending is likely to be slightly higher in real terms next year despite the new caps.”