The government’s strategy: divide and conquer

We consider the government’s incentives by assuming that its primary objective is to remain in power. While to a certain extent this is true of all political movements, in the Venezuelan case these incentives are exacerbated by the very high exit costs that government leaders appear to have. The fact that it is hard to visualize a transfer of power in which many government leaders do not end up facing prosecution suggests that the government will be willing to pay a very high cost to retain control of the presidency.

This line of reasoning immediately leads to the conclusion that the government could be willing to violate key democratic constraints. This could include rigging the election or suspending it altogether. However, these extreme alternatives are costly, especially in terms of the effects on national and international legitimacy. Therefore, the government’s first alternative would be to win an election in which the opposition participates, and whose results the opposition accepts.

The possibility of the government prevailing in an election that is not rigged does not sound so farfetched today as it may have seemed a year ago. The political developments of 2017, and in particular the ability of the government to prevail in the October gubernatorial elections, dramatically altered the view that many analysts and political actors had about its electoral competitiveness. On October 15, pro-government candidates took 17 of the country’s 23 governorships and 52.6% of the popular vote. While the vote tally appears to have been altered in an 18th race—that for the Bolívar governorship—it does not change the fact that government candidates took the bulk of votes cast nationwide.

Much theorizing and empirical investigation have been carried out since to account for what was a surprising result, in light both of opinion surveys and the magnitude of the country’s economic crisis. The strongest competing hypotheses that have emerged are that the results can be explained by (i) high abstention from potential opposition voters (ii) high capacity of mobilization among pro-government supporters.

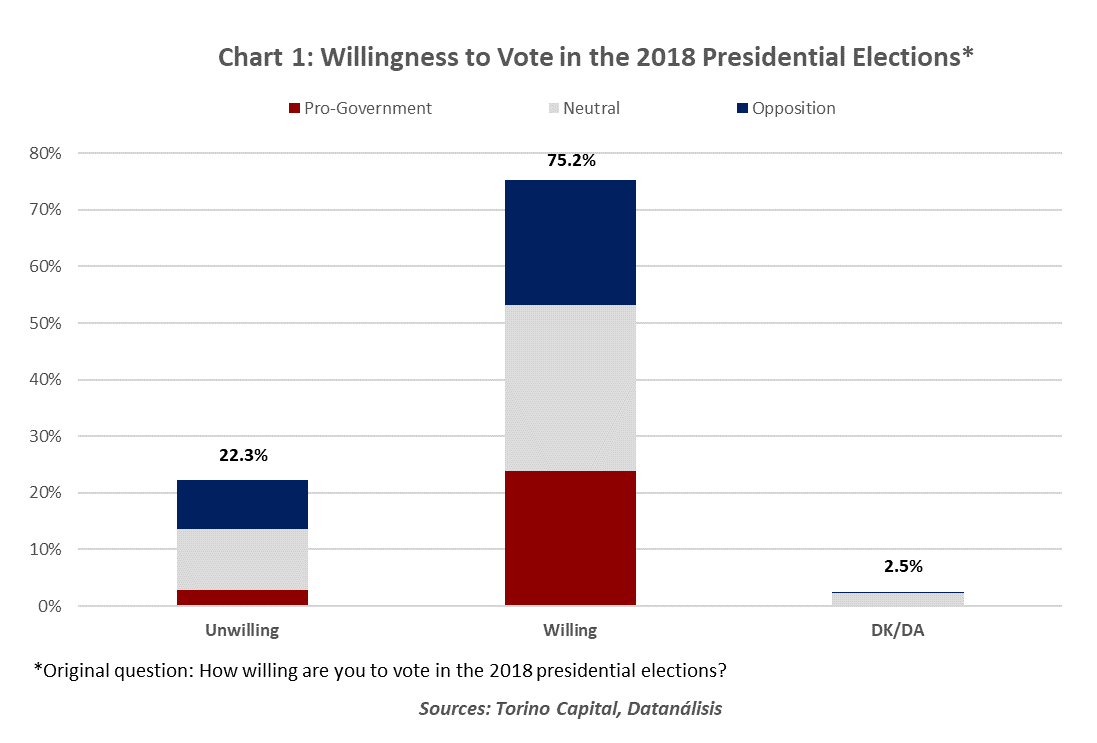

In this sense, it is clear that the government’s optimal strategy is to try to promote an electoral event in which it continues to mobilize its voters—for example by the deployment of selective incentives such as cash transfers—while fostering opposition abstention. Opposition abstention is, of course, a complex phenomenon, but a key contributing element is distrust of the electoral system. Thus, to the extent that the government can foster the impression that the system is rigged, then opposition turnout will be less and then—somewhat ironically—the government will have less need to rig it.

For these reasons, it made sense from the government’s standpoint to offer an agreement in the Dominican Republic negotiations in which it made some concessions to the opposition, but still kept control over key symbolically important aspects of the electoral process. For example, it is saying that the government’s final offer in these talks would have kept Tibisay Lucena—a staunch government loyalist—as the President of the Electoral Council (CNE). Regardless of the relevance of the CNE Presidency for the determination of the electoral results, the government was aware that many opposition voters would remain skeptical that the election could be clean as long as Lucena heads the CNE.

Faced with the refusal by the MUD delegation to sign the Dominican Republic accords, the government nevertheless decided to call the election, rather than give in to the opposition’s demand for improved conditions, including a delay of the election date. Partly, the government’s calculation must have relied on the hope that some opposition groups would participate. This split would generate the most advantageous political field—an opposition split between abstentionists and advocates of participation—and would give the government the legitimacy of winning a contested election.

On the other hand, it is worth recalling that chavismo has been strengthened by electoral boycotts in the past. A prominent example is the 2005 legislative elections, which was boycotted by the opposition and led the government to capture the entire National Assembly. Certainly, the international context was somewhat different, and the government’s legitimacy was much less in question at the time. However, memory of that experience continues to be an important driver of the government’s approach to electoral competition.

The MUD: between credible and incredible threats

Over the past year, the MUD has put forward an international communications strategy that has been extremely successful in isolating Venezuela’s government and characterizing it as a dictatorial regime. Perhaps the most recent example of the success of that strategy has been in the decision by Peru to revoke the invitation it had previously extended to Maduro to attend the Summit of the Americas on April 13 and 14.

As time went by, it became clear that the opposition needed to develop a strategy to confront the 2018 presidential elections. As we pointed out above, the electoral events of 2017 showed that an opposition victory in a presidential election was not necessarily a given. This forced a change of tactic from the MUD leadership. While it had spent much of 2016 and 2017 calling for early elections, in 2018 it shifted the focus to the conditions under which these elections would be held, and in arguing that it would only participate in free and fair elections.

There are, of course, many ways in which an election could fail to be free or fair. The most blatant one is actual rigging of the vote count. The CNE’s avowal of apparently distorted vote tallies in the October 15 Bolívar gubernatorial elections and in the July 30 Constitutional Convention elections suggests that there are good reasons to fear that the actual election result could be subject to a similar distortion.

But it is not clear why this would be a reason for the MUD not to participate in these elections. The Bolívar results, in fact, showed that, while it is possible for the CNE to distort the vote tally, it is very easy to detect that vote alteration, as it produces inconsistencies between the final vote count and the polling station records kept by opposition witnesses. If the MUD candidate were to in fact obtain more votes than Maduro in the presidential election but the CNE were to alter that vote count, the opposition could use that event to further delegitimize the government and rally national and international support in its favor. There are in fact many examples in which authoritarian governments have been forced to give up power after losing an election which they tried to rig.

The MUD’s fears rather appear to have more to do with the other elements of the electoral system which it considers unfair and which could lead it to obtain fewer votes than the government. Had the MUD signed the Dominican Republic agreement, it could have ended up committing to recognizing the results of an election played on an unlevel playing field. Two examples of these governmental advantages are the imposition of severe restrictions on Venezuelans’ right to vote outside of the country, and the use by the government of selective incentives to reward voters, including the giving of cash and in-kind payments on election day.

It is still the case that the opposition could have opted to not sign the Dominican Republic agreement and nevertheless decided to participate in the elections. This would have required a communications strategy that characterized the elections as unfair but painted electoral participation as another act of resistance against the government.

One way to understand the MUD’s decision is as a result of extreme risk aversion. MUD leaders believe that the Maduro government is already seen internationally as illegitimate and dictatorial. There is thus little to gain even from winning the election—on the assumption that the government would rig the vote count anyway. But there is a lot to lose from participating in the election and losing it, to the extent that some actors perceive participation as an acceptance of the rules of the game.

But how does the election boycott lead to regime change? The assumption must be that advancing on a strategy of regime delegitimization would inevitably lead to external pressure on the government to increase. A ratcheting up of sanctions on the government and its officials would generate a deterioration of economic conditions such that it would ultimately lead the government coalition to crumble. Seeing the situation as unsustainable, and with the economy starved of resources, the military would ultimately turn on Maduro and produce regime change in order to regain governability. Some actors in the opposition may also believe that this dénouement would involve some more explicit international action to drive Maduro from power.

Third party actors: little to lose and a lot to gain

One of the key problems with the MUD’s strategy of boycotting the elections is that it generates a significant incentive for third-party actors to defect from it and choose to participate in the elections. Top MUD leaders may believe that they have too much to lose from failing to win an election, but this may be less of a problem for third-party leaders who do not play a dominant role in the MUD and which would be unlikely to be picked to head a MUD government in case the Maduro government collapsed.

A key figure in this map is Henri Falcón, the former governor of Lara, who has spent the last ten years courting middle-of-the-road voters that feel disenchanted with chavismo but who do not feel represented by the opposition either. Falcón has been openly critical of some of the most extreme tactics of the opposition and the United States: his party has openly condemned U.S. sanctions and voted against the National Assembly’s attempt in January of 2017 to declare that Maduro had left the position of the presidency vacant.

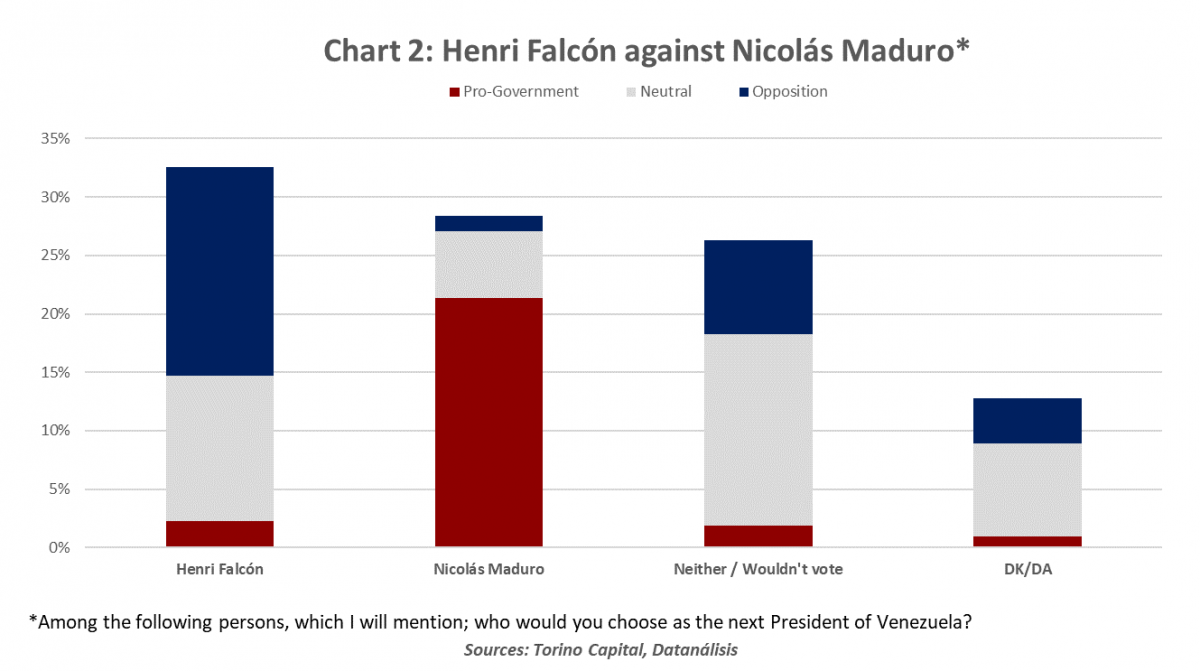

Since Falcón’s primary support lies among non-MUD voters, he has a lot less to lose from alienating opposition hardliners—many of whom would not vote for him if they were able to choose another opposition figure. On the other hand, current opinion polls show him beating Maduro in a two-way contest, even allowing for high opposition abstention (Chart 2).

For example, a Datanálisis tracking poll carried out between February 8 and 16 put Falcón ahead with 32.6% of the vote compared to Maduro’s 28.4%. The remainder of voters claimed they would vote for neither of these candidates (26.3%) or did not answer the question (12.8%). If we take the total of valid responses as the denominator, these totals indicate that Falcón would win the election with 53.4% of the vote compared to Maduro’s 46.6%—a 6.9-point lead. The poll was based on 800 interviews and has a margin of error of ±3.4%.

Interestingly, the poll shows that uncommitted voters are mainly neutral or opposition voters. Only 10.1% of chavistas remain uncommitted, while 37.0% of opposition voters and 55.8% of neutral voters remain uncommitted. Among those who are committed, Falcón captures 68.3% of neutral voters and 93.0% of opposition voters. This implies that Falcón would have significant potential to increase his advantage if he were able to cut into opposition and neutral voter abstention. Thus, while it appears that a 6.9-point lead may be too small to claim victory in an unlevel playing field, there is definitely potential for that advantage to grow over time if there is an effective strategy to convince opposition and neutral voters.

Falcón is not the only independent opposition candidate. Claudio Fermín, a former mayor of Caracas and Acción Democrática presidential candidate in 1992, has also announced his intention to run for the presidency, while Javier Bertucci, an evangelical pastor, launched his bid on February 18. However, polls point to Falcón as the front-runner in this field. In the Datanálisis poll, Falcón was the top choice of voters with 16.8% of respondents, compared to Fermín’s 4.6%.

Scenario I: Deepening authoritarianism

Against this backdrop, it is possible to imagine two broad scenarios developing. In the first, Maduro is re-elected for another six-year period. This is because either Falcón and other third-party candidates decline to run or they prove unable to prevail against the government’s superior electoral machinery. For the purposes of this scenario, whether Maduro actually “wins” in terms of getting the majority of votes cast in his favor—or instead loses but is able to rig the vote count in his favor—may be of little relevance. The election is unlikely to be recognized by most of the international community as valid, and thus the consequences are likely to be the same as if no election had been held.

We expect the United States to react to this development by tightening economic sanctions, including the adoption of a prohibition on exporting oil products to Venezuela as well as ultimately a ban on oil imports into the United States. It is hard not to visualize an acute further deterioration of economic conditions in Venezuela as a result of these actions, given the high integration of Venezuela’s oil industry into U.S. markets. There is also a clear risk of other countries in the region and Europe adopting financial and broader economic sanctions. We expect prospects of an orderly restructuring of the country’s external debt to dim as it becomes increasingly isolated economically.

We also expect the Venezuelan government to further consolidate its political control in society in this scenario. In all likelihood, the MUD will disavow the election results and therefore claim that Maduro is not the Constitutional President of Venezuela for the 2019-2025 period. It is likely that the National Assembly will move ahead to appoint a new government in the absence of a legitimate government, in which case the government could move ahead and accuse the legislative branch of sedition. [2]

Would the deterioration of economic conditions provoke the regime change scenario sought by opposition leaders? It is possible, but we remain skeptical that this is the most likely direction that events will take. There are numerous examples of authoritarian governments—Cuba, Syria, Zimbabwe to name just three—in which deteriorating economies and external sanctions have reinforced the hold of leaders in power. In non-competitive political regimes, the ability of governments to remain in power depends mainly on the relative power of the state vis-à-vis the rest of society, making it possible for the government to consolidate its power even as society becomes more impoverished.

Scenario II: Electoral upset ushers in regime change

In a second scenario, the third-party candidate consolidates his lead in the polls and manages to beat Nicolás Maduro in the elections. Taking this scenario seriously implies believing that the government will not choose to rig the vote count or to suspend the elections when its electoral defeat becomes clear. A given assumption in this scenario is that key power groups such as the military move to force Maduro to recognize his loss rather than run the greater risk of annulling the results altogether.

We envision this process as necessarily one of a negotiated transition, along with the lines of that which occurred in Chile after Augusto Pinochet lost the 1988 plebiscite or in Nicaragua when Daniel Ortega lost his 1990 re-election bid. In fact, we would distinguish between the act of winning the election—defined as receiving more votes than the incumbent—and successfully negotiating the transition.

It is worth noting that the scheduling of elections in April implies that there will be a lame-duck period of more than eight months between the election date and the date on which the new president takes office. It is possible that there could be an agreement to shorten this period, but we see this as more likely to happen in the context of broader negotiations designed to create institutions that set the ground rules for cohabitation between the incoming administration and chavismo.

This complex negotiation would have to balance the demands of key power groups in the outgoing government with the demands of the opposition as well as key international actors. Its success will hinge on the capacity of the new authorities to convince key actors that a negotiated transition is the safer path towards the consolidation of democracy, even if it requires concessions such as the design of transitional justice mechanisms.

About the Author

About the Author

Francisco Rodríguez is the Chief Economist of Torino Capital LLC. Previously, he was Director and Senior Andean Economist at Bank of America Merrill Lynch New York. Rodríguez has held numerous positions in academia and public policy. He has taught economics at the University of Maryland at College Park, Wesleyan University, and the Institute for Advanced Management Studies (IESA) in Caracas. Before joining BAML, Rodríguez was the head of research at the Human Development Report Office at the UN Development Program. His research has been published in journals such as Foreign Affairs, American Economic Journal, and Journal of Economic Growth. He is the co-author of Venezuela before Chávez (Penn State University Press, 2012). He holds a PhD in economics from Harvard University.

Notes: