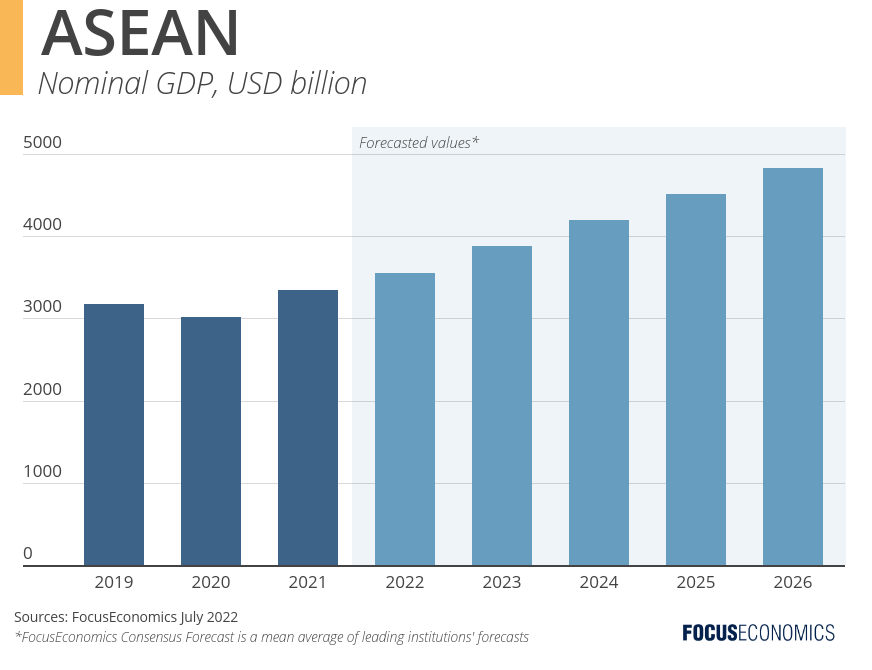

ASEAN—the Association of Southeast Asian Nations—is a trade bloc covering 10 Asian economies, including Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Over the last 20 years, the bloc’s cumulative GDP in nominal terms has risen from a mere USD 600 billion to USD 3,300 billion in 2021. Over our forecast horizon to 2026, GDP is seen rising to USD 4,800 billion, with average annual growth of close to 5%. If these projections are realized, they would make ASEAN the fifth largest economy in the world—behind only the U.S., China, Japan and Germany.

A series of factors are fueling the region’s development. Favorable demographics are one: the population is currently growing by around six million per year, and around 60% of people are under the age of 35. The bloc’s outward-looking trade policy is another important driver. In late-2020, the bloc secured a trade pact with other Asian neighbors called RCEP for instance, and many ASEAN members also participate in the Pacific-Rim CPTPP. This trade policy is boosting the region’s manufacturing base, and helping it secure the investment of firms looking to relocate from China. Relatively stable domestic politics—with the notable exception of Myanmar, which suffered an army-led coup in 2021—is also aiding economic activity.

That said, the gap in growth projections among member states is large. At one end of the scale is Myanmar, which our analysts expect to contract 1.3% this year. At the other are the dynamic economies of the Philippines and Vietnam, with forecasts of 6.9% and 6.7% growth respectively.

Moreover, to unlock its full economic potential, ASEAN must still surmount several obstacles. One crucial outstanding task is deepening the bloc’s internal market. While goods tariffs have been largely eliminated among members, a host of non-tariff barriers remain, and as such ASEAN is still a much looser economic union that other trading blocs, such as the EU or NAFTA. Increasing resilience to climate change is another, given the already-prevalent tropical storms and other extreme weather events in the region. Maintaining friendly trade relations with both the U.S. and China is another challenge in a context of increasing belligerency between the two global powers.

Insights from Our Analyst Network

On relations with the U.S and China, the EIU said:

“We believe that ASEAN will not choose sides between the US and China. ASEAN leaders view the growing risks of bifurcation of the economic and military spheres of influence with alarm, as these could have profound implications on their trade and manufacturing activities as well as technology adoption. ASEAN will strive to stay engaged with both camps. While welcoming more proactive engagements by the US in the region, ASEAN nations will be careful not to antagonise or downgrade their ties with China. They will balance their relationships with both powers.”

On Joe Biden’s recent proposed U.S.-Asia cooperation framework, analysts at Nomura said:

“Participating nations, especially the ASEAN countries, may be wary of being included in a U.S. strategy to counter China in the region that at this point appears to place burdens on them without providing any clear benefits, such as greater access to the U.S. market— sort of a “carrot and stick” strategy that lacks “carrots.” This concern may be one reason why Indonesia will begin negotiating an FTA with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), whose members include Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Armenia and Kyrgyzstan.”