On 23 September, the British chancellor announced a radical “mini-budget”. It included billions of pounds of debt-financed tax cuts and was bereft of the usual accompanying fiscal forecasts from the OBR, the independent fiscal watchdog. This came soon after the new Prime Minister Liz Truss government announced a freeze on energy bills which could cost well over GBP 100 billion over the next two years. When asked in an interview what was next for policymaking, the chancellor stated that there was “more to come”—considered by many as a hint that further tax cuts are in the pipeline.

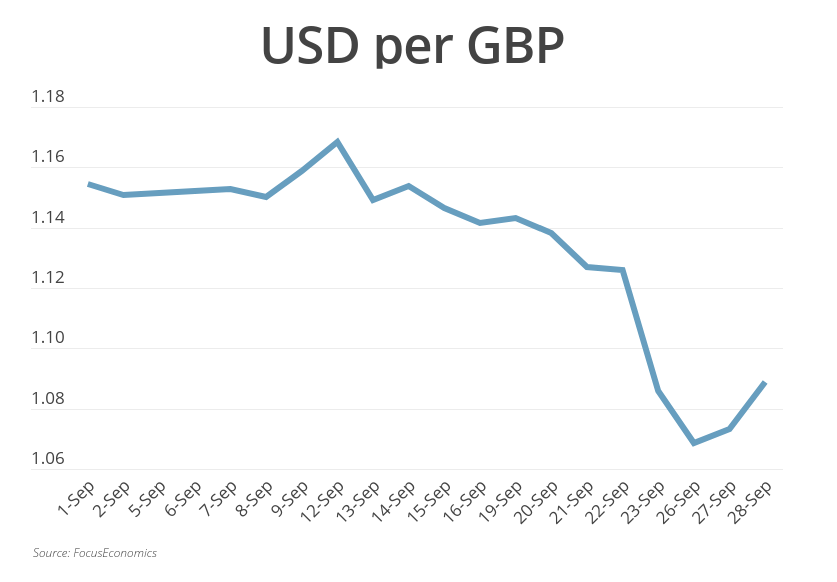

The market’s rebuke has been both swift and stern: The pound has depreciated by around 7% in the last week, while 10-year government bond yields have rocketed to 4.5%—close to the levels of debt-laden sovereigns Greece and Italy—compared to slightly over 3% before the mini-budget. Several institutions have suspended mortgage provisions due to the financial market gyrations.

So, where does this leave the economy? For one, the pound will remain depressed until the government offers greater assurances of fiscal prudence. These could come in late November when the chancellor will set out the government’s medium-term fiscal plan, this time in conjunction with OBR projections. Second, the budget deficit and public debt will be higher in the medium-long term than under the previous prime minister. Finally, economic activity could get a short-term boost from the extra fiscal stimulus, although this will be partially offset by greater demand-push inflation and tighter financial conditions.

Much will depend on how the Bank of England (BoE) reacts. The Bank has already announced a bond-buying program to soothe financial markets and stabilize gilt yields. And it seems highly likely that over the next year the BoE will hike by more than previously expected to tame price pressures and support the pound. Aggressive hiking could deepen the recession our analysts have already penciled in for the coming winter.

There is even growing market speculation over whether the UK will face a balance of payments crisis in the near term, given waning investor sentiment and the multi-decade high current account deficit forecast for this year. This appears unlikely for now. Sterling remains one of the five reserve currencies, anchoring demand for British assets. And the government’s debt is denominated in pounds, meaning its liabilities don’t increase as the currency depreciates. But in light of recent developments, the risk of such a crisis has certainly increased. It may not be there yet, but the UK is certainly in danger of reprising its decades-ago role as the sick man of Europe.

Insight from Our Analyst Network

On the currency, analysts at ING said:

“Sterling has fallen close to 10% on a trade-weighted basis in a little under two months. That’s a lot for a major reserve currency. And traded volatility levels for the pound are those you would expect during an emerging market currency crisis. […] At this stage, we think UK authorities will probably just have to let sterling find its right level. The UK has a reserve currency so it can always issue debt – it’s just a question of the right price.”

Regarding monetary policy, economists at Nomura said:

“While an emergency hike cannot be ruled out, we don’t expect the Bank to engage – after all, not only could an emergency hike rattle the markets (again), but it would likely reflect either the Treasury having not fully briefed the MPC on its fiscal package or the MPC having failed to act appropriately at the September meeting –which could reflect poorly on both the government and the Bank, respectively. This week, however, we have taken the opportunity to revise up our forecasts for forthcoming monetary tightening and now expect 75bp in both November and December, then 50bp in February and 25bp in March 2023 for a peak Bank Rate of 4.50%. We have also removed our forecast of policy easing from our rate profile in H2 2023.”